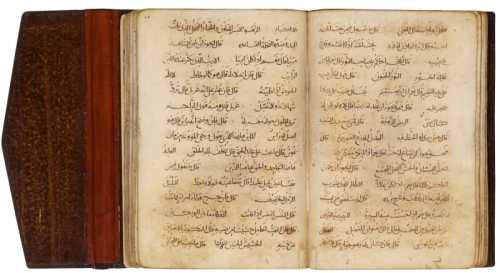

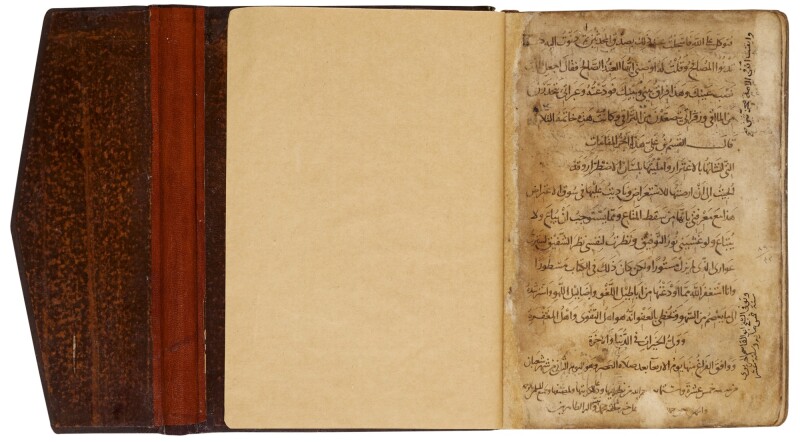

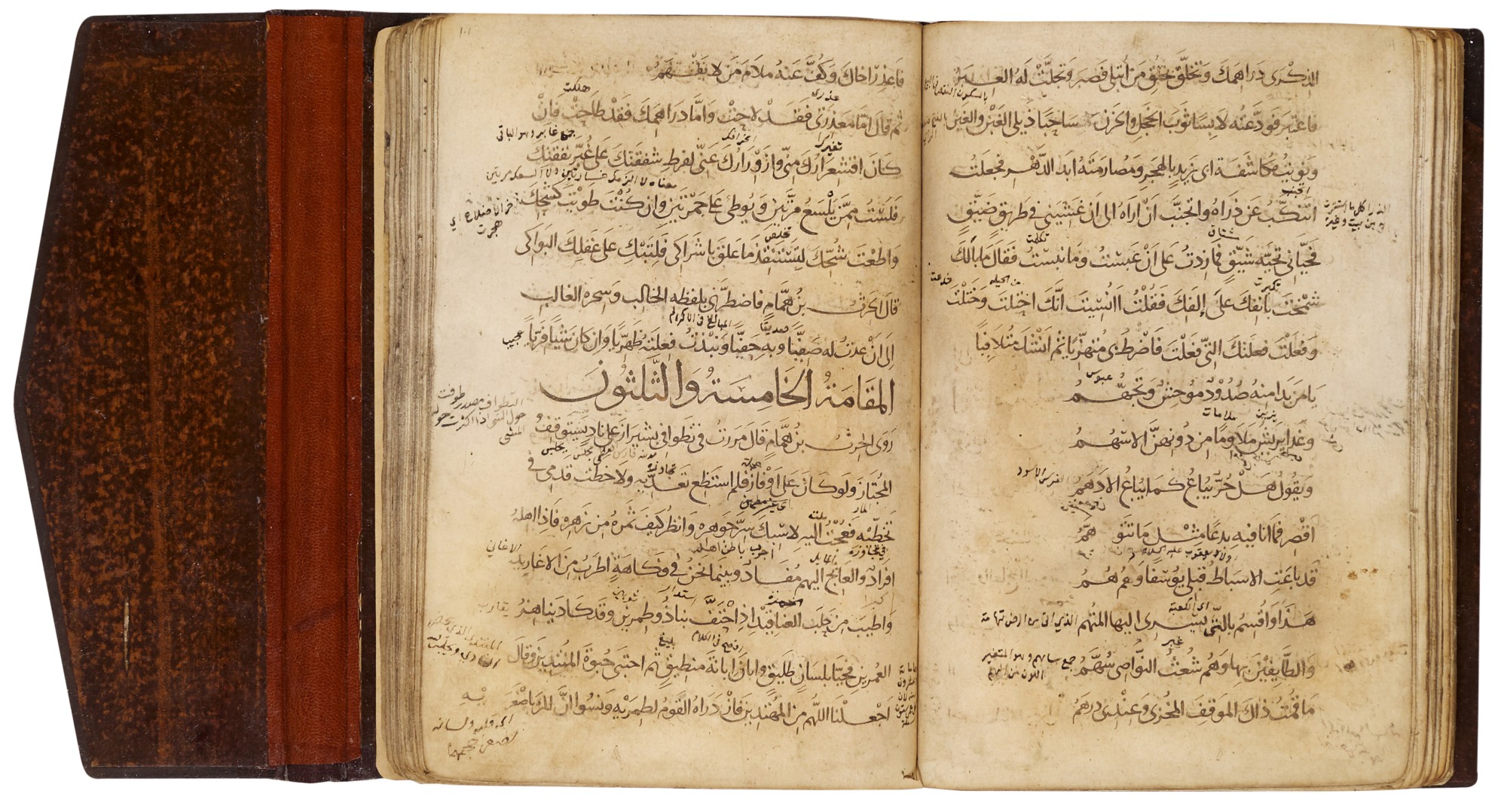

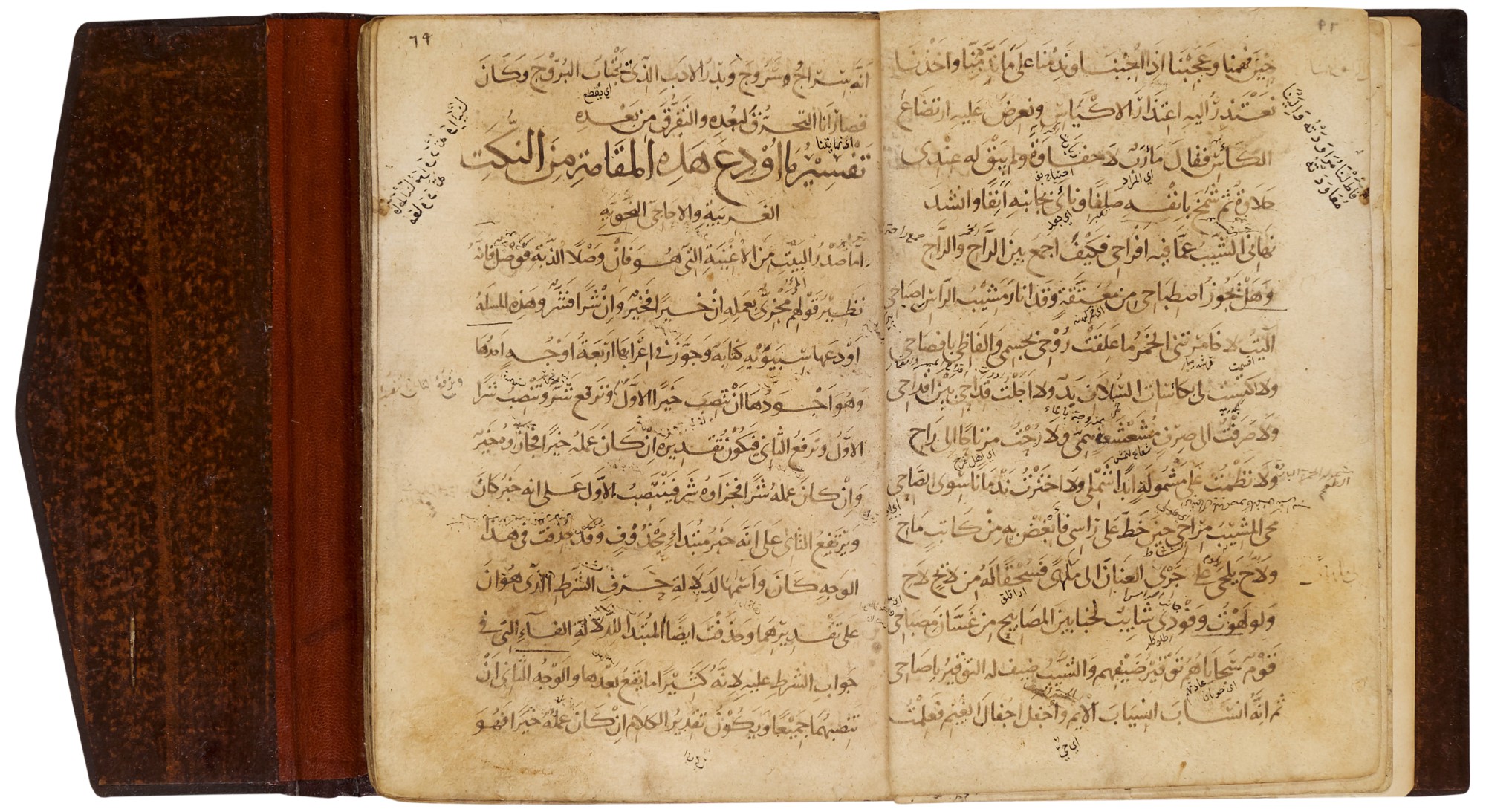

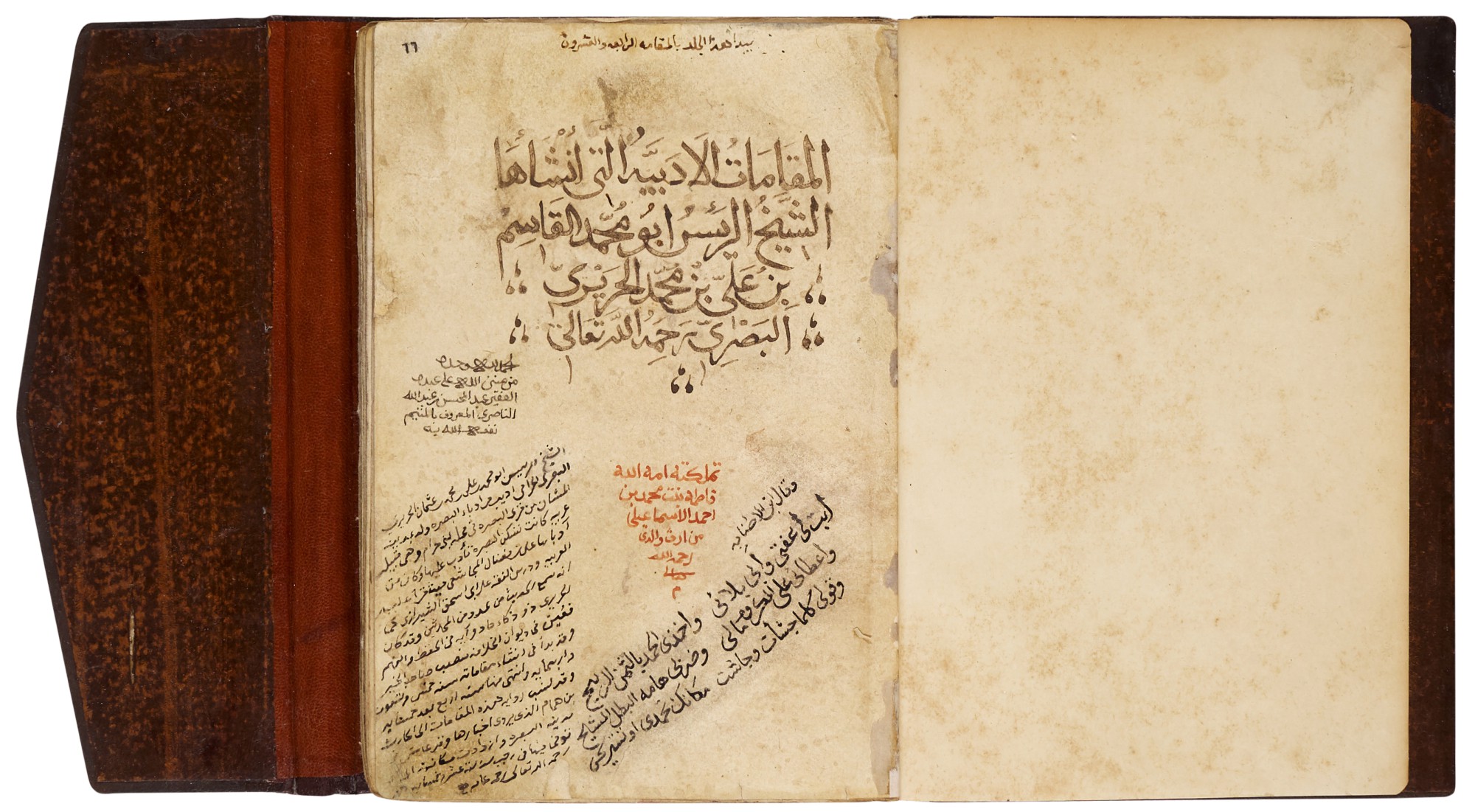

- Abu Muhammad Al-Qasim ibn Ali Muhammad ibn Uthman Al-Hariri (d.1122), also known as al-Hariri al-Basri, al-Maqamat (second half), Near East, dated 2 Sha’ban 615 AH/24 October 1218 AD

- Handicrafts and classics, Calligraphy, manuscript

- 15.2 * 22.5 cm

- Arabic manuscript on cream thick paper, 99 leaves plus 2 fly-leaves, 15 lines to the page written in neat and elegant naskh in dark brown ink, titles in thuluth, in brown leather binding decorated with a central stamped round medallion, with flap

Estimation

£40,000

52,356 USD

-

£60,000

78,534 USD

Realized Price

£50,400

65,969 USD

0.8%

Artwork Description

“What the maqamah did was to invest with the literary graces of saj' [rhymed prose] and the glamour of impromptu composition the old-time tale in alternate prose and verse….. and, by a stroke of genius, to adopt as the mouthpiece of [its] art that familiar figure in popular story, the witty vagabond” (Kritzeck 1964, p.180). This is among the earliest copies of al-Hariri’s masterpiece, copied only one century after the death of the author.

Abu Muhammad al-Qasim ibn Ali Muhammad ibn Uthman al-Hariri was born in Basra, today in Iraq, in 1054-55. The name Hariri was likely connected with the profession of his father, who used to trade in silk (harir). Coming from a wealthy family, with extensive possessions around Meshan, he was a pupil of al-Fadl al-Kasbani and later became a government official assuming the title of Sahib al-Khabar (Chenery 1867, p.11). Along with his masterpiece Maqamat, he is also the author of two treatises on grammar which both show his magnificent talent and knowledge of the Arabic language (Chenery 1867, p.12).

The word maqama means ‘setting’ or ‘session’ and the Maqamat presents itself as a collection of stories, all linked by a common narrator. This genre was not new to Arabic literature and, although there is no consensus on the father of this genre, Badi al-Zaman Hamadhani is surely the most illustrious predecessor (for a extensive discussion on the matter and additional information of Hamadhani, please see the Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/badi-al-zaman-hamadani-abul-fazl-ahmad-b). Hamadhani’s Maqamat was a collection of stories narrated in rhymed prose (sajʿ), and according to the legend, his Maqamat contained more than four hundred stories, although today’s version has only fifty-two chapters. Hamadhani's text was considered a model for al-Hariri’s.

The text is composed of fifty short stories, each identified by a name of a city of the Muslim world in which the main characters, al-Harith and Abu Zayd, meet. The narrator is al-Harith, who tells the adventures of the peripatetic Abu Zayd. Abu Zayd is an incredible orator and survives thanks to his rhetoric, a quality which enables him to persuade and evade punishment when in need. Only in the last maqama does Abu Zayd repent and admit his sins.

The corpus is notable for the language used, the different rhetorical styles and al-Hariri’s genius and ability to work with the Arabic language. As noted by Allen, “Al-Hariri provides examples of linguistic virtuosity that is unparalleled in Arabic literature” (Allen 2000, p.164). Each maqama is an example of his ability with language. This volume presents the second half of Hariri’s masterpiece, beginning at the twenty-fourth maqama and ending at the fiftieth. As noted by Irwin, “it is impossible to understand Hariri’s Maqamat without a commentary, and indeed after the Qur’an this book has attracted more commentaries than any other Arabic book” (Irwin 1999, p.188). Alongside marginal annotations, this copy includes two tafsir after the twenty-fourth and after the twenty-seventh maqama.

The first illustrated copies of al-Hariri’s Maqamat were produced at the beginning of the thirteenth century, and six copies dated to this period survive, two of which are attributed to Syria in the first quarter of thirteenth century, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris (one undated - Arabe 3929 and one dated 1222 AD - Arabe 6094). Two other illustrated manuscripts were made in Baghdad and are attributed to the 1230s (one attributed to 1225-35 AD is now in St Petersburg, Academy of Sciences, inv. no.s23; one in the Bibliothèque National, Paris, dated 1236-37 AD, Arabe 5847) and two copies produced towards the mid-thirteenth century (one is in Suleymaniye Library, Istanbul, inv. no.2916 and one in the British Library, London, Or.1200). A copy attributed to thirteenth-century Baghdad was sold in these rooms, 15 October, 1984, lot 289, while another one dated before 677 AH/1278 AD was sold in these rooms, 1 May 2019, lot 12.

Other early-dated but unillustrated copies of the Maqamat are listed as follows: Ms. Cairo Adab 105 can be dated 504/1110-11 through an ijaza note of al-Hariri himself; another dated 557 AH/1161-62 AD (London, British Library, Or. 2790); a third dated 583 AH/1187 AD (Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Sbath 265), a fourth dated 584 AH/1188 AD (Paris, BnF, Arabe 3924), a fifth dated 611 AH/1214 AD (Paris, BnF, Arabe 3926), and a sixth dated 611 AH/1214 AD (Paris, BnF, Arabe 3927). See Peter MacKay, 'Certificates of Transmission on a Manuscript of the Maqamat of Ḥariri (MS. Cairo, Adab 105)' in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 1971, Vol.61, No.4, (1971), pp.1-81.

More lots by Abu Muhammad Al-Qasim ibn Ali Muhammad ibn Uthman Al-Hariri

No artworks

Realized Price

65,969 USD

Min Estimate

52,356 USD

Max Estimate

78,534 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+0.8%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates