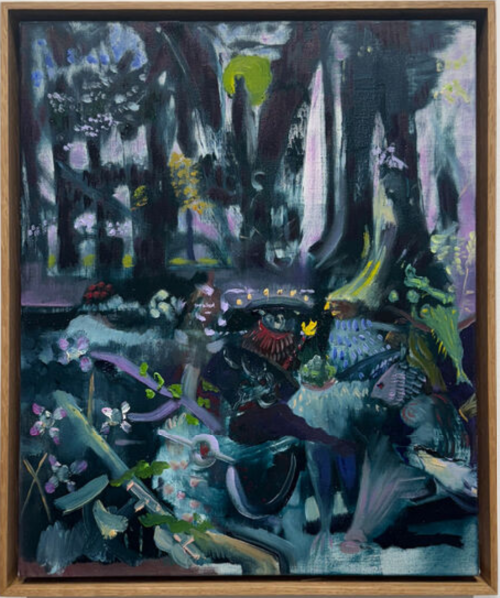

- Before the Name 2015

- oil on linen

- Painting

- 40.5 * 40.5 cm

Artwork Description

“Sometimes I forget what I put in. I want to capture things in that way, where you're looking into your memory, a dream or hallucination. The characters become a mixture of archetypes, [and] that's what I like. You're trying to figure it out and your brain wants to categorize things, but it can't because of this motion…I sometimes say the conflict in the work is the conflict of my own thoughts and anxieties. It's a civil war in my head. The top part [of my artwork] is you letting go and floating. You become part of the air and you've tapped into the heartbeat of the universe.”

(A. Banisadr, quoted in conversation with B. Groys, in Ali Banisadr: One Hundred and Twenty-Five Paintings, London 2015, p.25).

Before the Name is an intense, powerful work by Ali Banisadr, one of the most well-known contemporary Iranian artists today, noted for his apocalyptic and colorfully dense compositions. Combining elements of Iranian miniatures, New York City style graffiti, Renaissance Venetian and Flemish painters and Japanese woodblock prints, his works recount fragile memories of his past. His compositions are a meeting place where consonance and dissonance meet, and where feelings of anguish and seclusion fall within pockets of joyful notes. Through his works, one draws references to the great Venetian artists he admires, specifically Jacopo Tintoretto (1519- 1594) and the Gothic Flemish painter, Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516). He also draws inspiration from the graffiti he grew up around in San Francisco from artists such as Barry McGee (b. 1966) and Margaret Kilgallen (1967-2001).

Conjuring memories from the eight year Iran-Iraq war, along with other elements of pop culture, cinema, and graphic novels, these distant recollections of childhood memory have come to inhabit his subconscious, as he visualizes this sheer violence with figures and monumental expanses. For Banisadr, painting is fundamentally rooted in his experience of synesthesia: a neurological condition where the stimulation of one sensation triggers another, such as seeing sounds or tasting words, most likely triggered from his childhood in war-torn Iran. His paintings’ titles such as the present work suggest a sense of otherworldliness and mayhem bordering on darker, violent language, such as Burn it Down, Infidels, Crash and Time for Outrage.

The present work exemplifies a near-cinematic explosion of line, gesture and form combining circular and geometric shapes a gestural clashing of colours and organic forms which invade the canvas. The work captures the seemingly eternal moment that reigns in the duration of a blast: a sense of time collapsing inwards on itself, of centuries replayed in a split second, and of the nameless clarity that emerges only in the very depths of chaos. This disorder is emphasized by the contrast of the background, which features sharp lines and colors that appear flat, and the overwhelming foreground, which explodes towards the viewer. This is narrated as if we can hear the sounds of war-time Tehran, where missile attacks, chemical weapons and air strikes were common instances

(A. Banisadr, quoted in conversation with B. Groys, in Ali Banisadr: One Hundred and Twenty-Five Paintings, London 2015, p.25).

Before the Name is an intense, powerful work by Ali Banisadr, one of the most well-known contemporary Iranian artists today, noted for his apocalyptic and colorfully dense compositions. Combining elements of Iranian miniatures, New York City style graffiti, Renaissance Venetian and Flemish painters and Japanese woodblock prints, his works recount fragile memories of his past. His compositions are a meeting place where consonance and dissonance meet, and where feelings of anguish and seclusion fall within pockets of joyful notes. Through his works, one draws references to the great Venetian artists he admires, specifically Jacopo Tintoretto (1519- 1594) and the Gothic Flemish painter, Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516). He also draws inspiration from the graffiti he grew up around in San Francisco from artists such as Barry McGee (b. 1966) and Margaret Kilgallen (1967-2001).

Conjuring memories from the eight year Iran-Iraq war, along with other elements of pop culture, cinema, and graphic novels, these distant recollections of childhood memory have come to inhabit his subconscious, as he visualizes this sheer violence with figures and monumental expanses. For Banisadr, painting is fundamentally rooted in his experience of synesthesia: a neurological condition where the stimulation of one sensation triggers another, such as seeing sounds or tasting words, most likely triggered from his childhood in war-torn Iran. His paintings’ titles such as the present work suggest a sense of otherworldliness and mayhem bordering on darker, violent language, such as Burn it Down, Infidels, Crash and Time for Outrage.

The present work exemplifies a near-cinematic explosion of line, gesture and form combining circular and geometric shapes a gestural clashing of colours and organic forms which invade the canvas. The work captures the seemingly eternal moment that reigns in the duration of a blast: a sense of time collapsing inwards on itself, of centuries replayed in a split second, and of the nameless clarity that emerges only in the very depths of chaos. This disorder is emphasized by the contrast of the background, which features sharp lines and colors that appear flat, and the overwhelming foreground, which explodes towards the viewer. This is narrated as if we can hear the sounds of war-time Tehran, where missile attacks, chemical weapons and air strikes were common instances

Realized Price

218,606 USD

Min Estimate

125,765 USD

Max Estimate

178,204 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+54.349%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

Similar Artworks

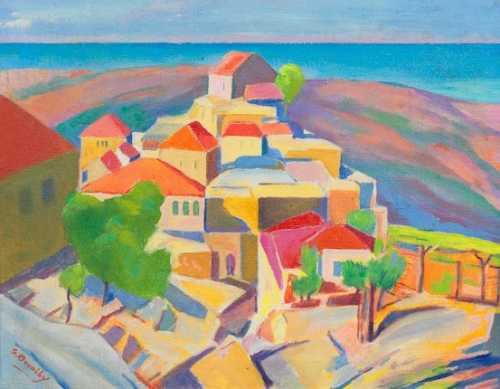

Le village de Aitou

Estimation

£30,000

38,067 USD

-

£50,000

63,445 USD

Realized Price

£57,550

73,026 USD

43.875%

Sale Date

Bonhams

-

5 June 2024