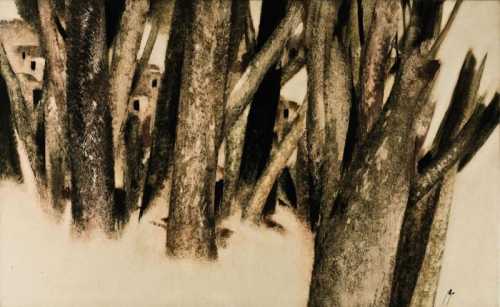

- Untitled (from the 'Mother of the National Hero' series) 1960 - 1969

- Oil on canvas

- Painting

- 125 * 95 cm

20 October 2021

Estimation

£140,000

193,424 USD

-

£180,000

248,687 USD

Realized Price

£237,500

328,129 USD

48.438%

Artwork Description

‘…the agony dissolved gradually into lyricism, until Sabri’s hell-tormented men and women began to emerge as though in a trance of joy. It was Sabri’s interest in a shared, practiced identity—one in which broad sectors of Iraqi society took part, either as active participants or witnesses—that motivated his turning towards popular rituals, which he used to reflect upon current political issues.’

– Jabra Ibrahim Jabra on Sabri’s 1960s works

This evocative masterpiece by Iraqi pioneer Mahmoud Sabri comes from his acclaimed ‘Mother of the National Hero’ series and was produced around the same time period as his sought-after 'Funeral of the Martyr' series. Through Sabri’s critical writing and painting oeuvre, the artist is long recognised as one of the most important figures in building the foundations of Modern Iraqi art and acts as an important point of departure from the other known figures of the Iraqi art scene, including Jewad Selim and Faeq Hassan, among others who were set in depicting Iraqi heritage. This work’s powerful and haunting composition incorporates numerous recurring elements within his oeuvre, and its monumental size and intriguing history makes it a museum quality work representative of the most important and emotionally-wrenching decade of the artist's production.

Works of Sabri from this period are found in the collections of the Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah and MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha. The artist has gained critical attention with a posthumous retrospective in La Galleria Pall Mall, London, co-organised by Yasmin Sabri, the artist’s daughter and Iraqi artist Satta Hashem.

Furthermore, this work was recently rediscovered by the Artist’s Estate who managed to retrieve and restore it. Its physical condition was found punctured in places across the composition, perhaps deliberately by the artist, as if to evoke war scars symbolising the poignant and emotional turbulence at the time. It is believed that the artist may have destroyed this work, although it cannot be fully confirmed. Nevertheless the sheer story serves as a chilling reminder of the artist’s self-imposed exile and the turbulent state of Iraq at the time.

Although holding a crucial role in the Iraqi modern art movement, Sabri’s place in history has perhaps been unfairly shadowed by the fact that he stood strongly against the many themes that other artists of the time were exploring. As a rebel against the current political status of Iraq of the day, Sabri wrote a manifesto asserting his political stance against the fascist nature of the Ba’ath Party. This manifesto, and his constant agitation towards the party, ultimately led to his self-exile. The artist’s opinion about current affairs and socialistic theories helped to establish an assorted awareness in Iraq and the Middle East pushing a development in artistic expression.

In 1960 Sabri left for Russia to study at the Surikov Institute of Art under the artist Alexander Deyneka, who was very impressed with his work. While there, Sabri was inspired by Russian icons, sculpture and paintings. Departing for Russia caused many to believe that the artist was pro-Communist. Sabri's style following this period shows a direct link stylistically to iconography with a palette that reached beyond his classical use of blacks and reds.

Amidst this landscape surfaced key art groups such as the Baghdad Group for Modern Art, led by Jewad Selim and Shaker Hassan Al Said in 1951, and Ar-Ruwwad (the Pioneers) founded by Faeq Hassan in 1950. Belonging to Ar-Ruwwad, Sabri was keen to paint on the streets ‘directly from the surrounding environment’ – oftentimes visiting Iraq’s rural areas.

Due to the changing political climate of 1950s Iraq which developed a deep rift between the higher and lower classes, involvement in the life of the hardships of the poor and dispossessed became a distinguishing mark of a majority of Iraqi art in the early and mid-1950s. During this time Sabri was preoccupied with using his works to highlight social and political issues and the plight of the people, his agony became partly political, partly existential and so the treatment of his social themes was full of pain, protest and anger depicting revolutionaries, poverty, floods and demonstrations; his individuals became characterised by a leanness and toughness that cemented Sabri's stance on social issues.

In 1953, a young man named Numan Mohamed Al Saleh was proclaimed a martyr, whose death instigated a large processional funeral that was attended by thousands of people in their defiance against the regime and revolt against the situation of the lower and working classes. This event inspired Sabri to begin a series of works under the title Janazet Al Shaheed, marking 12 years of reworking and revisiting multiple versions, which matured as an increased sense of intensity in his thinking pushed the way he looked at the funeral as a topic of struggle and sacrifice in the face of death.

Sabri was known to produce multiple iterations of a composition, as evident in the comparable illustrations shown. Heavy in symbolism, the work incorporates three interlinking elements within his oeuvre - the horse and rider, the martyr, and crowds. Existing in their own separate spaces within the composition against an abstract sea-green background, one can detect the influence of Christian icons and communist idealogies. The woman holding the martyr symbolises a weeping and desolate Iraq; she is clutching, faintly touching and lamenting over the death. The hierarchy and careful placement of the figures, a reference to the Christian Icons Sabri admired, is flanked by two elements of nationalist fervor: a man alongside his horse, a symbol of pride and endurance juxtaposed with four figures holding spades for the burial: the spade another symbol heavy with communist tendencies. These elements appear as if to impart the sense that communism is not dead, but rather will live on with the people and indicates the Ba'athists' taking power will have on future generations.

The Martyr’s disposition appears almost angelic, mirroring the Virgin Mary and Christ, bringing with it a signifier towards both enlightenment and revolution. Although tragic, the work is a strong reminder of the fierce resilience of the Iraqi people. Their chiselled features, abstract, harsh lines and prominent eyes, serve to highlight the intensity of the commemorated event—in this case, paying homage to the martyr through the act of mourning.

– Jabra Ibrahim Jabra on Sabri’s 1960s works

This evocative masterpiece by Iraqi pioneer Mahmoud Sabri comes from his acclaimed ‘Mother of the National Hero’ series and was produced around the same time period as his sought-after 'Funeral of the Martyr' series. Through Sabri’s critical writing and painting oeuvre, the artist is long recognised as one of the most important figures in building the foundations of Modern Iraqi art and acts as an important point of departure from the other known figures of the Iraqi art scene, including Jewad Selim and Faeq Hassan, among others who were set in depicting Iraqi heritage. This work’s powerful and haunting composition incorporates numerous recurring elements within his oeuvre, and its monumental size and intriguing history makes it a museum quality work representative of the most important and emotionally-wrenching decade of the artist's production.

Works of Sabri from this period are found in the collections of the Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah and MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha. The artist has gained critical attention with a posthumous retrospective in La Galleria Pall Mall, London, co-organised by Yasmin Sabri, the artist’s daughter and Iraqi artist Satta Hashem.

Furthermore, this work was recently rediscovered by the Artist’s Estate who managed to retrieve and restore it. Its physical condition was found punctured in places across the composition, perhaps deliberately by the artist, as if to evoke war scars symbolising the poignant and emotional turbulence at the time. It is believed that the artist may have destroyed this work, although it cannot be fully confirmed. Nevertheless the sheer story serves as a chilling reminder of the artist’s self-imposed exile and the turbulent state of Iraq at the time.

Although holding a crucial role in the Iraqi modern art movement, Sabri’s place in history has perhaps been unfairly shadowed by the fact that he stood strongly against the many themes that other artists of the time were exploring. As a rebel against the current political status of Iraq of the day, Sabri wrote a manifesto asserting his political stance against the fascist nature of the Ba’ath Party. This manifesto, and his constant agitation towards the party, ultimately led to his self-exile. The artist’s opinion about current affairs and socialistic theories helped to establish an assorted awareness in Iraq and the Middle East pushing a development in artistic expression.

In 1960 Sabri left for Russia to study at the Surikov Institute of Art under the artist Alexander Deyneka, who was very impressed with his work. While there, Sabri was inspired by Russian icons, sculpture and paintings. Departing for Russia caused many to believe that the artist was pro-Communist. Sabri's style following this period shows a direct link stylistically to iconography with a palette that reached beyond his classical use of blacks and reds.

Amidst this landscape surfaced key art groups such as the Baghdad Group for Modern Art, led by Jewad Selim and Shaker Hassan Al Said in 1951, and Ar-Ruwwad (the Pioneers) founded by Faeq Hassan in 1950. Belonging to Ar-Ruwwad, Sabri was keen to paint on the streets ‘directly from the surrounding environment’ – oftentimes visiting Iraq’s rural areas.

Due to the changing political climate of 1950s Iraq which developed a deep rift between the higher and lower classes, involvement in the life of the hardships of the poor and dispossessed became a distinguishing mark of a majority of Iraqi art in the early and mid-1950s. During this time Sabri was preoccupied with using his works to highlight social and political issues and the plight of the people, his agony became partly political, partly existential and so the treatment of his social themes was full of pain, protest and anger depicting revolutionaries, poverty, floods and demonstrations; his individuals became characterised by a leanness and toughness that cemented Sabri's stance on social issues.

In 1953, a young man named Numan Mohamed Al Saleh was proclaimed a martyr, whose death instigated a large processional funeral that was attended by thousands of people in their defiance against the regime and revolt against the situation of the lower and working classes. This event inspired Sabri to begin a series of works under the title Janazet Al Shaheed, marking 12 years of reworking and revisiting multiple versions, which matured as an increased sense of intensity in his thinking pushed the way he looked at the funeral as a topic of struggle and sacrifice in the face of death.

Sabri was known to produce multiple iterations of a composition, as evident in the comparable illustrations shown. Heavy in symbolism, the work incorporates three interlinking elements within his oeuvre - the horse and rider, the martyr, and crowds. Existing in their own separate spaces within the composition against an abstract sea-green background, one can detect the influence of Christian icons and communist idealogies. The woman holding the martyr symbolises a weeping and desolate Iraq; she is clutching, faintly touching and lamenting over the death. The hierarchy and careful placement of the figures, a reference to the Christian Icons Sabri admired, is flanked by two elements of nationalist fervor: a man alongside his horse, a symbol of pride and endurance juxtaposed with four figures holding spades for the burial: the spade another symbol heavy with communist tendencies. These elements appear as if to impart the sense that communism is not dead, but rather will live on with the people and indicates the Ba'athists' taking power will have on future generations.

The Martyr’s disposition appears almost angelic, mirroring the Virgin Mary and Christ, bringing with it a signifier towards both enlightenment and revolution. Although tragic, the work is a strong reminder of the fierce resilience of the Iraqi people. Their chiselled features, abstract, harsh lines and prominent eyes, serve to highlight the intensity of the commemorated event—in this case, paying homage to the martyr through the act of mourning.

More lots by Mahmoud Sabri

Four Faces

Estimation

£12,000

16,559 USD

-

£18,000

24,838 USD

Realized Price

£35,280

48,682 USD

135.2%

Sell at

Sale Date

Sotheby's

-

20 October 2021

Untitled (Portrait of a Boy)

Estimation

£25,000

32,895 USD

-

£35,000

46,053 USD

Sale Date

Christie's

-

11 November 2025

H20 + AG + AiR (From the Quantum Realism Series)

Estimation

£50,000

66,667 USD

-

£80,000

106,667 USD

Realized Price

£95,650

127,533 USD

47.154%

Sale Date

Bonhams

-

25 November 2025

Realized Price

94,932 USD

Min Estimate

53,913 USD

Max Estimate

77,002 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+44.783%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

Similar Artworks

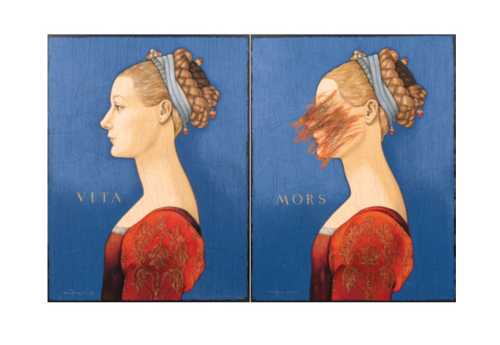

Mors - Vita (from the Memories of Destruction series)

Estimation

100,000,000,000﷼

200,000 USD

-

120,000,000,000﷼

240,000 USD

Realized Price

145,200,000,000﷼

290,400 USD

32%

Sale Date

Tehran

-

24 January 2024