Tehran,

No. 69/1, Sepand alley South Aban St., Karimkhan Zand St.

17 December 2021 - 27 December 2021

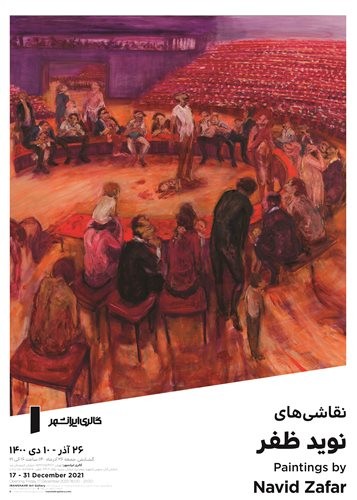

Funny Games

A reflection on the paintings of Navid Zafaralizadeh

“Getting to act” is the theme of the works of Navid Zafaralizadeh; that is, staging the “play,” (through action) as such. The tragic, bitter aspect of his work is the theatricality of these plays. In a sense, it is staging and getting everything to act. As such, “playing” up to insanity, mangling each other in the most ghastly way, or playing with children to the point of their being slaughtered. In other words, creating an unrestrained mob, or in an accumulation of idle distorted figures, among faces reminiscent of the “maschere” of commedia dell’Arte, their only difference being that there is no mask on these faces; rather, what has distorted them is an all-over metamorphosis. Individuals with distorted mouths laughing boisterously while doing the most outrageous deeds, not only in public, but in the form of a dramatic work on stage and, finally, an audience of the same type, sitting indifferently, looking at the play of players whose hands are dirty with blood, or laughing and making faces… These theatrical aspects have become a characteristic of Zafaralizadeh’s paintings. In other words, he has not only been able to use them as subject matter but has benefitted greatly from the dramatic workings of theater in advancing his own work. Why should this experience of painting be regarded as “staging”? Having in mind that the definition of the theatrical stage draws its meaning from the crowd of living individuals on it, what is the particularity and significance of the painted scenes with the theatrical stage? Or, what does it mean (here) for the painting to become dramatic? In order to respond, one should know that the painter makes his subject matter theatrical in order to highlight the dramatic element of disasters. In a sense, he is not content to just display or paint mishaps. Rather, he strives to keep the subject matter of his paintings dramatic while they are being seen, as such, spectacularizing them in great gatherings. In his paintings, each event is displayed with no trace of concern in front of hundreds of gazes, like today’s society as a whole which has turned into a vitrine, a spectacle Guy Debord called The Society of the Spectacle, the age in which everything is consumed through its becoming an spectacle, or nothing has remained of it other than “externalness” and spectacle. Thus, here the most frightening nightmares have found their way to the stage through painting to become spectacular in public view… an allusion to the sheer indifference of people who are willing to leisurely view the century’s disasters from the comfort of their seats. Next, Zafaralizadeh spectacularizes the whole scene and its spectators for the ones who view the paintings from a distance. In a sense, we are looking at such horrifying spectacle of a crowd from outside, with the presumption that seeing as viewing is an essential term of every spectacle. Painting and theater both are viewed. As Rancière has said: “viewing is also an action … [The spectator] observes, selects, compares, interprets. She links what she sees to a host of other things that she has seen on other stages, in other kinds of place. She participates in the performance by refashioning it in her own way.” This feature is an attribute of any kind of seeing in every aspect. And the painter’s proposal is to view these “Funny Games” inside the painting’s frame. Put more simply, what he does is to introduce a distance between two ways of seeing, creating a division representing the distance between people as the spectators of the spectacle (inside the painting) and us as the ones standing outside and viewing the painting as a whole, defining a frontier to make the act of viewing act or make the viewer’s perception flow, a space that “is owned by no one, whose meaning is owned by no one, but which subsists between them [the actor and the spectator],” as Rancière puts it. It is there where we are emancipated, or are played with or we ourselves play. Rancière calls such an spectator “the emancipated spectator:” “It is in this power of associating and dissociating that the emancipation of the spectator consists – that is to say, the emancipation of each of us as spectator. Being a spectator is not some passive condition that we should transform into activity. It is our normal situation… [it is in this encounter that the spectator makes her story]. Every spectator is already an actor in her story; every actor, every man of action, is the spectator of the same story… That is what the word ‘emancipation’ means: the blurring of the boundary between those who act and those who look; between individuals and members of a collective body,” … between the one who callously slaughters his/her fellowman and maybe one of us who is viewing his/her act, or changing the place of one of our fellowmen with a spectator there, in the painting, sitting and laughing to any of our wounds …

— Mohammad Parvizi

(Translated by Parisa Hakim Javadi)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

— “Funny Games”: an allusion to the concept of game in the horrific violent ambience of the movie Funny Games (2007), directed by Michael Haneke

— See Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, translated into English by Gregory Elliott, Verso Books: London.

— Commedia dell’arte: a convention of popular theater born in Italy in early 16th century

— Maschere: mask and also the types of characters in commedia dell’arte