About Farrokh Mahdavi

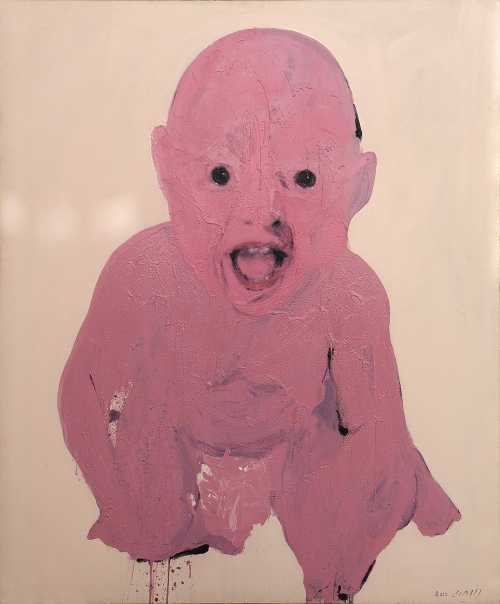

Farrokh Mahdavi, a contemporary painter, is known for his grotesque single faces. The physical nature of the paint and the pink color are the signatures of Mahdavi's paintings. Mahdavi exhibited his works for the first time in Homa Gallery in 2009. This work attracted the art community's attention and paved the way for his strong presence in galleries inside and outside the country. Attending a group exhibition at Westminster University in London in the same year was Mahdavi's first international experience. In 2011, his artworks were exhibited in "How lucky we are, an angel on our table and God in our car" at the Krenzinger Gallery, Vienna. In 2013, Etemad Gallery hosted Mahdavi's second solo exhibition, "Hearts." In 2015, he participated in a group exhibition titled "The Big Game" at the 56th Venice Biennale.

In the first period of his career (between 2008 and 2015), Mahdavi used to paint figures and faces abstractly and used pink color by removing the sidelines of the facial features and minor references to the location of each of them. The pink pigment in this period is muted and dull. It does not have a mass character and sits on the surface of the canvas as a rub. Of course, in this interval, there are glimpses of his desire to use mass paint and the resulting texture in the collection of hearts. From the beginning of the 2010s, the mass characteristic of paint material gradually entered Farrokhi's single faces and became the central quality of his works. The paint in this period (unlike its function of it before) sits like a layer of paste on the face's surface, burying the person's identity. In these paintings, parts of the face (such as the nose or parts of the jaw) realistically protrude from the edge of this paste, which explains the pink paint's masking nature.

In the next period of Mahdavi's works, a collection known as "Eslah-e-Bozorg," with the addition of a razor that removes parts of this texture and reveals the face underneath, this feature has become more tangible and bold. On the other hand, this paste layer gradually becomes more voluminous and tends to have purer and brighter degrees of pink. Mahdavi has a witty and satirical tone in the representation of faces (from the angle of drawing the faces to the bulging eyes and their crooked mouth against the mirror/audience) and the pink color itself. Although this humor finds its depth with a subtle twist of bitter and biting pink, it ends up grotesque. The core of this grotesque should be found in the question of identity. Covering the faces with a mysterious layer destroys all the components of the people of the painting's identity.

In an interview, Mahdavi spoke about his experiences of the eight-year war and his encounter with corpses' impact. Because every time he and his comrades saw a decomposed body and tried to guess his identity. Because of these experiences, the transformation of a person's identity after death becomes his mental concern: "By removing a person's creditable marges such as his clothes, face or even his skin during an incident, a new independent identity is formed. This past later played a significant role in my figurative curiosities." In this sense, it might not be wrong to interpret the pink paste layer as the mask of death that sits on the faces and obscures the person's identity. In this case, the choice of pink as a symbol of death gives more formidable dimensions to the grotesque hidden in Mahdavi's paintings.

In the next period of Mahdavi's works, a collection known as "Eslah-e-Bozorg," with the addition of a razor that removes parts of this texture and reveals the face underneath, this feature has become more tangible and bold. On the other hand, this paste layer gradually becomes more voluminous and tends to have purer and brighter degrees of pink. Mahdavi has a witty and satirical tone in the representation of faces (from the angle of drawing the faces to the bulging eyes and their crooked mouth against the mirror/audience) and the pink color itself. Although this humor finds its depth with a subtle twist of bitter and biting pink, it ends up grotesque. The core of this grotesque should be found in the question of identity. Covering the faces with a mysterious layer destroys all the components of the people of the painting's identity.

In an interview, Mahdavi spoke about his experiences of the eight-year war and his encounter with corpses' impact. Because every time he and his comrades saw a decomposed body and tried to guess his identity. Because of these experiences, the transformation of a person's identity after death becomes his mental concern: "By removing a person's creditable marges such as his clothes, face or even his skin during an incident, a new independent identity is formed. This past later played a significant role in my figurative curiosities." In this sense, it might not be wrong to interpret the pink paste layer as the mask of death that sits on the faces and obscures the person's identity. In this case, the choice of pink as a symbol of death gives more formidable dimensions to the grotesque hidden in Mahdavi's paintings.

The Most Expensive Artwork

At Auctions

First Attendance

23 February 2021

# Attendance

6

# Artworks

6

Average Realized Price

11,843 USD

Average Min Estimate

9,397 USD

Average Max Estimate

12,761 USD

Sell-through Rate

100%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

9.28%

Timeline

Soft Edge of the Blade Vol. 3 exhibition

10 November

The 23rd Tehran - Modern and Contemporary Iranian Art auction

22 May

The 21st Tehran - Contemporary Iranian Art auction

11 October

The 18th Tehran Contemporary Art auction

12 December

Process exhibition

10 November

Prospect 3 exhibition

22 September

resize exhibition

13 April

Realism exhibition

13 April

Tehran- 16th- Iranian contemporary art auction

1 July

Vanishing Point exhibition

6 May

Soft Edge of the Blade exhibition

10 February

The 14th Tehran- Contemporary Iranian Art auction

12 August

Small Artworks collection exhibition

11 June

SOUTH SOUTH VEZA | LIVE VERNISSAGE & TIMED ONLINE auction

23 February

Encircle the Apple or Shadowlessness exhibition

27 September

Forty - Fifty - Sixty exhibition

21 June

Faces exhibition

7 June

2018 Collection Selling exhibition

17 January

The Shaving exhibition

13 October

The Big Shave exhibition

25 November

Art for Peace Festival exhibition

1 January

Articles

Iranian artists in Art Dubai 2024 6 January 2024

Art Dubai began in 2007 and over the past 17 years has established itself as a catalyst for the arts of the MENASA region in local, regional and international conversations. This art fair has also helped to place the art of these regions on the world map.Art Dubai 2024 will be held in March as usual. This event in four sections: Contemporary, Gateway, Modern and Digital also hosts I...