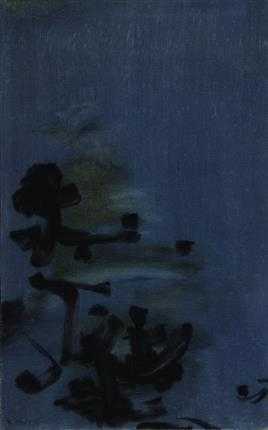

- Untitled 1971

- Oil on canvas

- Painting

- 89 * 129 cm

- signed "Nasser" and dated "1971" in English (lower right)

Auction Histories

Sell at

-

Auction House

26 April 2017

Realized Price

Artwork Description

Born in Tehran in 1928, Nasser Assar is one of the most seminal protagonists of the Iranian modernist movement. His works mark both a compositional departure from the academic formalism of the turn of the century, and a clear thematic circumvention of the dominant neo-traditionalist orthodoxy of his time.

His migration to Paris in the 1950s coincided with a critical juncture in the progression of European modernism. Still in its infancy, the French post-war art scene eventually gave rise to the establishment of Tachism and Lyrical Abstraction, movements which heavily influenced the work of Assar. However, whilst operating alongside luminaries such as Tapies, Fautrier, De Stael and Wou Ki, Assar still developed a unique and distinctive style of abstract expressionism which was neither derivative nor imitative of his European counterparts.

Assar's canvases are wrought with a strong sense of conceptual duality derived from the inner-collation of calligraphy and landscape. Taken compositionally, Assar's depiction are built up of pseudocalligraphic oriental letterforms set in an ethereal, polytonal landscape. Yet within the composition itself, letterforms and natural forms are inseparable, having seamlessly permeated their surroundings. This unrestricted oscillation between world and environment, aside from being technically progressive, itself serves as an aesthetic device for the expression of a far more profound artistic impulse whose genesis is found in the Zen calligraphy whose influence is so evident in Assar's work.

In the Zen Buddhist tradition, performing calligraphy, or hitsuzendo, is a meditative practice seminal towards the attainment of spiritual unity with the divine. In light of the universality of his practice, the language in which the calligraphy is composed becomes irrelevant, and Assar's choice to diverge from his native Persian, far from being an act of disregard, is merely an aesthetic affirmation of his belief in the transcendental and universal characteristics of divine truth. Concurring with the Sufi tradition, this entails an understanding of the world which treats worlds, languages and systems of communication merely as names and symbols for illusory, transient, material objects, which cast a deceptive veil of sense experience over the unified, absolute, and singular underlying spiritual reality.

It this underlying reality which Assar attempts to penetrate, by demonstrating that the material landscape of our world is purely an artifact of our linguistic habits, and not a source of absolute truth. This is all achieved within an aesthetic which is both technically proficient and visually diverse, and whose freedom of hand evolves a spontaneity which is at once expressive and unrestrained.

Realized Price

16,849 USD

Min Estimate

11,109 USD

Max Estimate

15,860 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+87.186%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

Similar Artworks

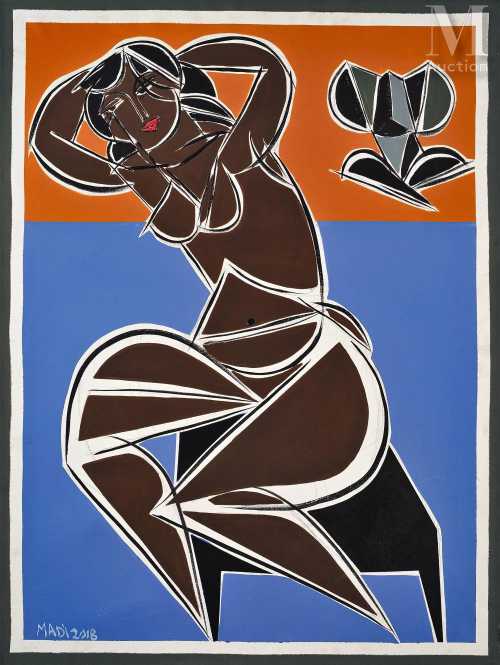

Untitled

Estimation

€46,000

49,094 USD

-

€64,500

68,838 USD

Realized Price

€48,000

51,228 USD

13.122%

Sale Date

Millon & Associés

-

25 April 2024

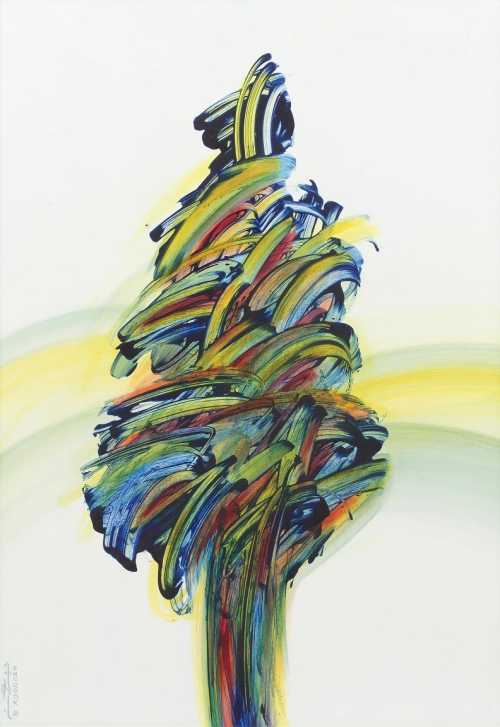

Untitled (Tree)

Estimation

£30,000

38,885 USD

-

£50,000

64,809 USD

Realized Price

£57,550

74,595 USD

43.875%

Sale Date

Bonhams

-

13 November 2024

The Lost Sea

Estimation

£40,000

53,763 USD

-

£60,000

80,645 USD

Realized Price

£57,550

77,352 USD

15.1%

Sale Date

Bonhams

-

21 May 2025