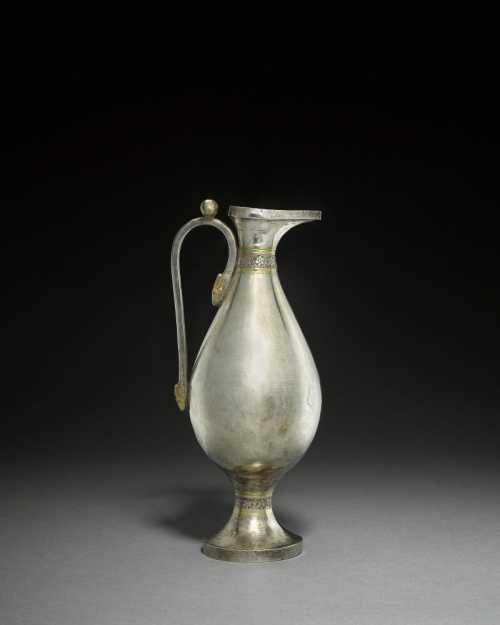

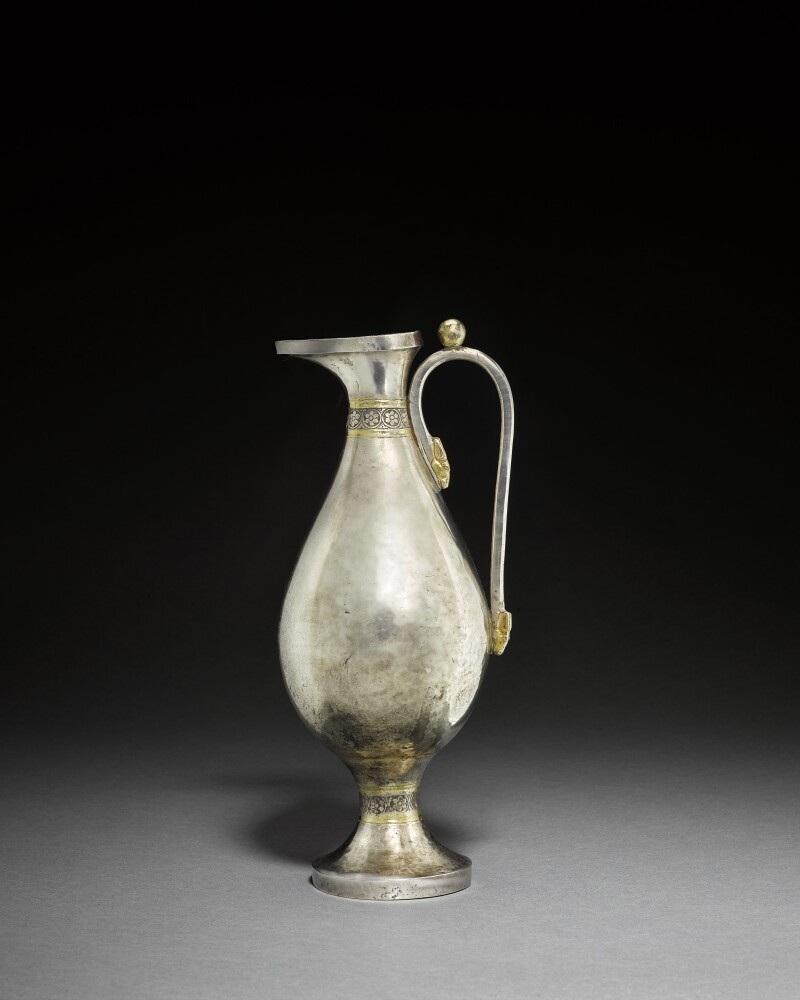

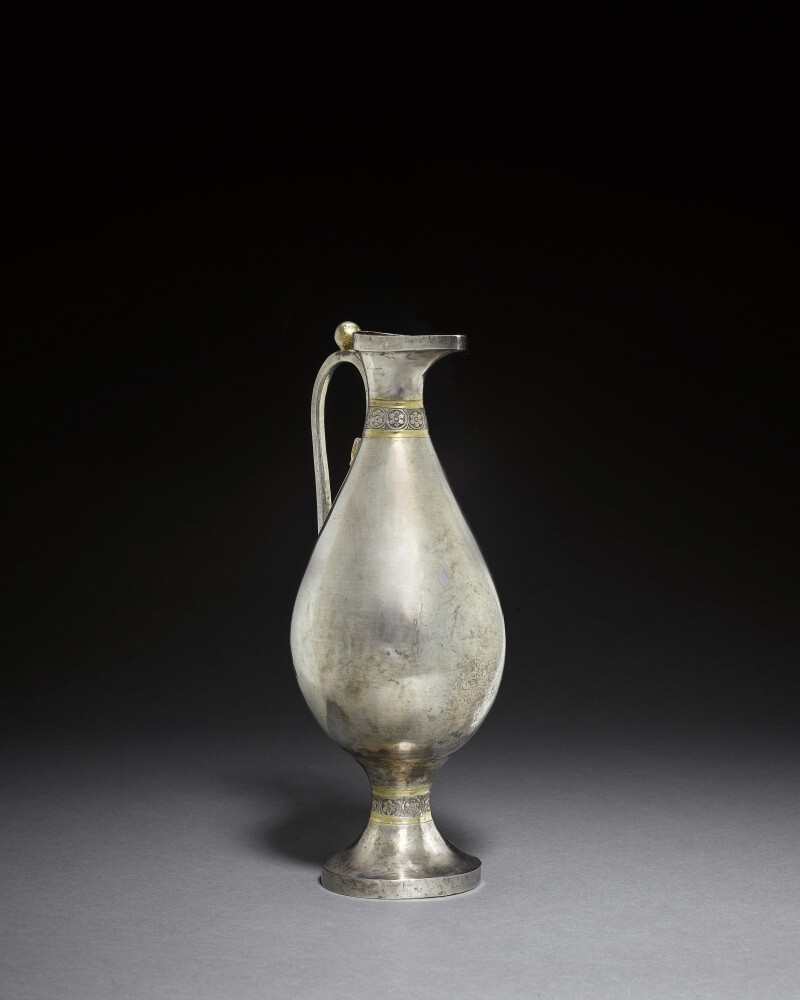

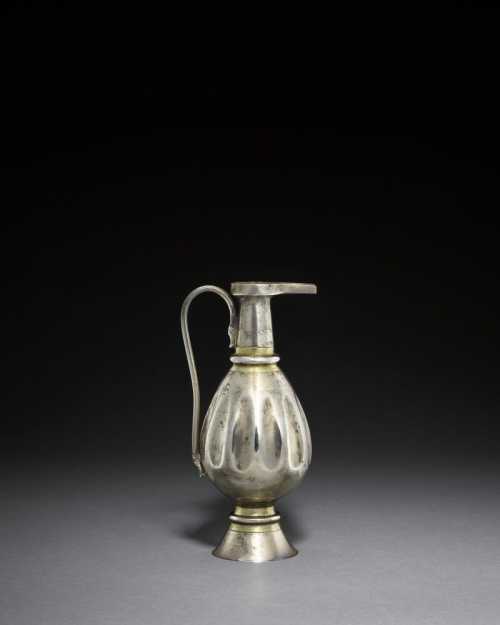

- A large Sassanian or early Islamic silver ewer, Persia, 7th-8th century

- Handicrafts and classics, Metal

- 34 cm

- of bulbous form, standing on a tall waisted foot, the tapering neck with a pointed spout, the scrolling handle surmounted by a gilt ball and attached to the neck and body by gilded terminals in the shape of onager heads, the foot and shoulder with a row of flowers between two gilt bands

Estimation

£60,000

78,534 USD

-

£80,000

104,712 USD

Unsold

Artwork Description

The present ewer and that of the following lot are typologically similar to vessels from the Late Sassanian Period. Their bulbous bodies are raised on flared conical feet, one reinforced by a vertical band providing the object greater stability and increasing its upright momentum. The present ewer has a gently tapering spout, while that of lot 84 has an open, flat end. The gilded zoomorphic heads at the extremities of the present lot's handle are clearly identifiable as those belonging to the onager, an Asiatic wild ass, and the protruding ball to the top was probably meant to strengthen the grip for a servant pouring wine. On both ewers, the body, foot and handle were worked separately: the first two parts were hammered on forming stakes, while the handles were probably cast in moulds. Based on similar examples, it may be assumed that they came with a lid, most likely a stopper that dropped into the neck.

Such ewers, distinguishable by a sober yet elegant decoration, were introduced in the Sassanian and Central Asian world in the fifth-sixth centuries and remained prized until the seventh century. Their shape and figural decoration suggest they were intended for domestic purpose. Onagers were animals typically hunted by the Persian aristocracy, and their head was a common decorative feature on silverware. In the case of the following ewer, the absence of a customary elevated border on the foot may indicate a more provincial origin or a slightly later dating (Overlaet 2018).

Another object that closely relates to our ewers, of comparable typology but entirely made of gold, comes from the princely tomb of Malaja Pereshchepina in south-west Ukraine, which contained a rich hoard of gold tableware - Sassanian, Turkish, Avarian and Sogdian in origin. Another is in the Hermitage Museum (inv. no.S-61) and was found in 1821 in a Russian village. Although it is tempting to interpret the presence of Sassanian items in diverse locations as evidence of diplomatic gifts, trade or booty, the spread of this type of objects have more complex implications. The Sassanian empire opened to many neighboring cultures, which it influenced as much as it assimilated. Von Petrikovits demonstrated that the shape of our ewers is particularly close to Roman or Early Byzantine models (von Petrikovits 1969), while their decoration points at Mediterranean later influence. While a similar ewer is represented on the rock relief of Khusrow II at Taq-e Bustan in Iran (see Fukai et al.1984), few exemplars were found directly on Sassanian territory. As such, it is difficult to determine if these ewers derive from import, imitation or direct and indirect influences within the Sassanian and early Islamic world (Overlaet 2018), but they certainly highlight the overwhelming reach of Persian tradition and the Silk Road in the fifth to seventh centuries.

More lots by Unknown Artist

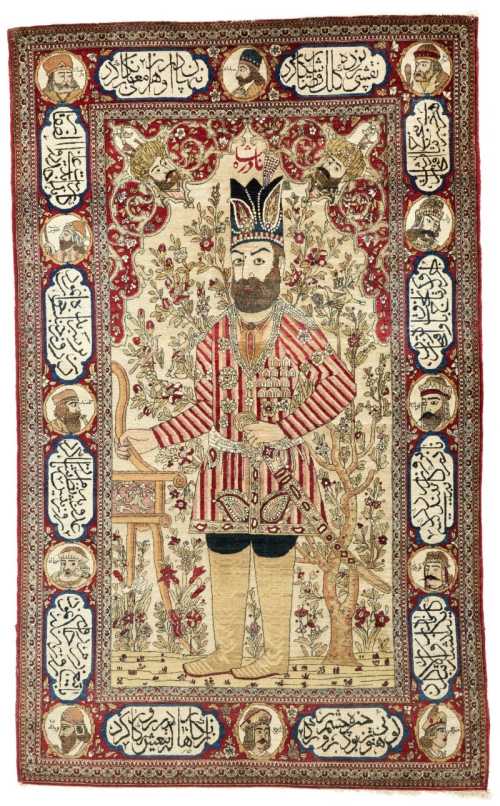

An Isfahan pictorial rug, Central Persia, circa 1910

Estimation

£4,000

5,236 USD

-

£6,000

7,853 USD

Realized Price

£5,670

7,421 USD

13.4%

Sale Date

Sotheby's

-

30 March 2022

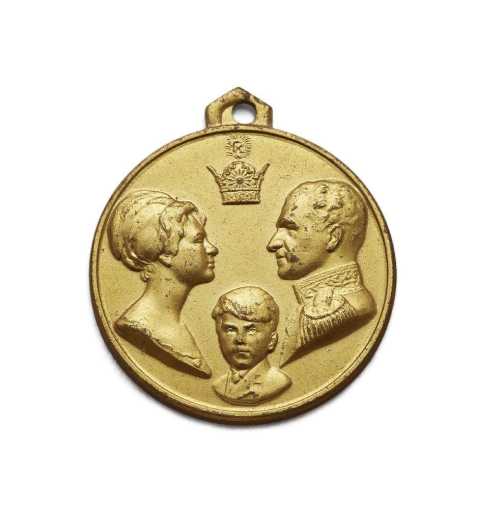

A gold medal commemorating the coronation of Muhammad Reza Shah and Queen Farah

Estimation

£100

132 USD

-

£200

263 USD

Realized Price

£160

211 USD

6.667%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

A silver memorial medal of the White Revolution, Muhammad Reza Shah, 1967

Estimation

£200

263 USD

-

£300

395 USD

Realized Price

£170

224 USD

32%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

Realized Price

67,245 USD

Min Estimate

35,481 USD

Max Estimate

53,247 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+83.63%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

Similar Artworks

A large inscribed bronze lidded incense burner with silver inlay, Iran, 13th century

A ceremonial brass engraved shield, Iran, 20th century

Estimation

£600

790 USD

-

£800

1,053 USD

Realized Price

£500

658 USD

28.571%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

A Sassanian or early Islamic silver ewer with vertical fluting, Persia, 7th-8th century

Estimation

£40,000

52,356 USD

-

£60,000

78,534 USD

Sale Date

Sotheby's

-

30 March 2022