- A fine and rare silver incense burner, Mesopotamia, Persia or Central Asia, 10th-12th century

- Handicrafts and classics, Metal

- 18.3 cm

- the body of cylindrical form with a high domical cover and bud-form finial, on three short angular feet, the long cylindrical handle rivetted to the body and decorated with grooved bands terminating in a slightly bulbous end-piece, the cover with openwork designs including bilobed or heart-shaped motifs and stylised lancet-leaf forms set in radiating petal-shaped cartouches with engraved borders and raised in shallow relief; the body with stiff upward-pointing leaves similarly decorated and raised in relief, with a pair of sculpted hinges in the form of fleur-de-lys rivetted on one side and part of a further hinge of fleur-de-lys form on the other side (possibly representing later additions), the interior later-fitted with pierced coal tray, with a pair of silver tongs18.3cm. height; 33.1cm. max. length; 11.5cm. diam. of bowl

Estimation

£250,000

327,225 USD

-

£300,000

392,670 USD

Realized Price

£315,000

412,304 USD

14.545%

Artwork Description

Raised from silver sheet and hammered into a powerful architectonic form reminiscent of a Central Asian domed building, this impressively large incense burner is a work of some technical merit and considerable art historical interest.

With its elegant, rounded form and confident, uncluttered approach to decoration, this refined piece is evidently the work of a skilled craftsman producing for a wealthy patron. Both technically and stylistically it relates to the well-known group of Ghaznavid high-tin bronze bowls of 11th/early 12th-century eastern Iranian origin. One noteworthy example is the Ghaznavid bowl in the al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait (inv. no.LNS 561 M) (Curatola 2010, p.92, no.64), which is decorated with divider-executed linear incisions with recessed fields struck and hammered into the surface, mirroring some of the ornamental aspects of the present piece.

The protruding tubular handle is also paralleled in eastern Iranian wares, such as the ninth/tenth-century bronze incense-burner also in the al-Sabah Collection (ibid, p.70, no.37). The latter, which is broader and heavier in design and execution, can be explained as a functional household utensil compared to the more sophisticated and precious, silver example. Another Khurasan bronze incense burner with long protruding handle is in Terres secrètes de Samarcande: Céramiques du VIIIe au XIIIe siècle (Paris 1992, p.28, no.331). Here again, the form and decoration is cursory in character and utilitarian in function. Further related bronze incense burners are published by Eva Baer (Baer 1983, pp.45-61) especially the two stupa-like examples in the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art, Jerusalem (inv. nos.M121-70 and M124-70; ibid, pp.49 and 51, figs.34-35). Few, if any, incense burners compare with the present example in terms of monumentality and formal grandeur. It is indeed a luxurious, princely, object.

Further comparison can be drawn to a fragmentary bronze ewer in the Louvre (inv. no.A.O. 7484), published in the Survey (Pope and Ackerman 1938-39, Vol.VI, pl.1282; and Paris 1977, p.158, no.325), which bears an arcade of raised petals separated by dimples or hammered depressions, echoing the motifs at the foot of the drum on the present incense burner.

Also at the foot of the drum of the ash-pan is an arcade of upward-pointing stiff lotus petals which reinforces the attribution to eastern Iran or Central Asia. The petal panel arcade is a recurrent decorative theme on Central Asian and Chinese silver and silver-gilt objects dating back to at least the Tang period (618-907), and is one of many Buddhist-derived motifs disseminated westwards, through trade and exchange, along the Silk Road. A similar lotus petal arcade is found on a silver-gilt cup in the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (inv. no.BM. 1132) attributed by Kramarovsky to "Golden Horde or Yuan Dynasty, 14th century" (The Treasures of the Golden Horde, St Petersburg, 2000, pp.110, 210, no.7).

Perhaps the closest technical and stylistic parallels can be found in the three similarly-shaped silver incense burners, attributed to 11th/12th-century Khurasan, which form part of the so-called 'Harari Treasure', now housed in the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art, Jerusalem (Pope and Ackermann 1938-39, vol.VI, pl.1352c-d; Ferrier 1977, p.174; Hasson 2000, p.41).

All considered, our incense burner belongs firmly to a sophisticated tradition of precious metal wares with its roots in Buddhist Central Asia and Tang China, though, in some of its formal aspects, it bridges the gap to the more utilitarian bronze artefacts of Khurasan, which naturally survive in far greater number.

A metallurgical report from Dr Peter Northover of the University of Oxford concludes that the composition of the incense burner is consistent with silver in circulation during the medieval period.

More lots by Unknown Artist

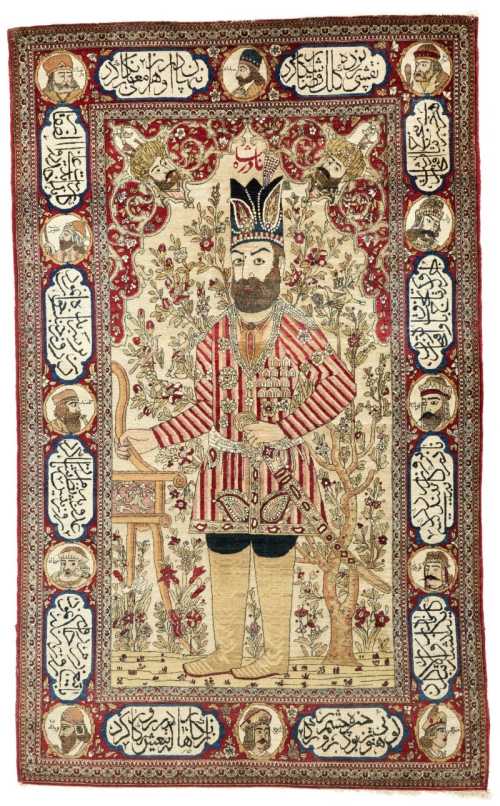

An Isfahan pictorial rug, Central Persia, circa 1910

Estimation

£4,000

5,236 USD

-

£6,000

7,853 USD

Realized Price

£5,670

7,421 USD

13.4%

Sale Date

Sotheby's

-

30 March 2022

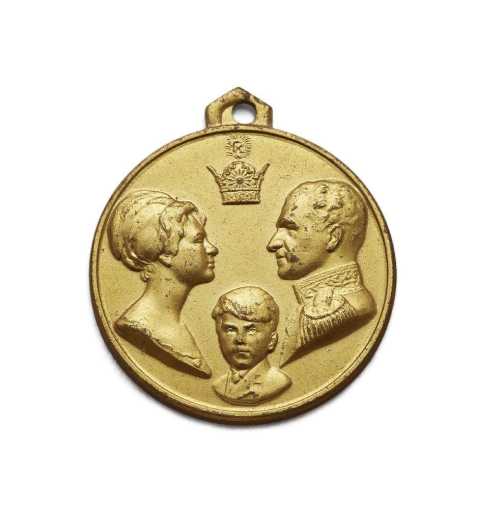

A gold medal commemorating the coronation of Muhammad Reza Shah and Queen Farah

Estimation

£100

132 USD

-

£200

263 USD

Realized Price

£160

211 USD

6.667%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

A silver memorial medal of the White Revolution, Muhammad Reza Shah, 1967

Estimation

£200

263 USD

-

£300

395 USD

Realized Price

£170

224 USD

32%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

Realized Price

67,245 USD

Min Estimate

35,481 USD

Max Estimate

53,247 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+83.63%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025