Marseille,

433 Boulevard Michelet, 13009 Marseilles.

1 July 2022 - 27 July 2022

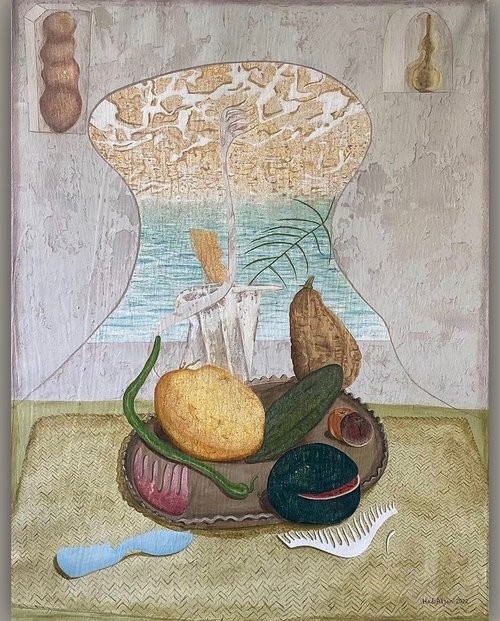

Hadi Alijani's exhibition is the result of his residency in Marseille at the Pavillon Southway in April 2022. We were keen to invite Hadi because of the posture of his work, and his view of history, which could be described as oracular vernacular.Hadi Alijani's practice is part of the long Persian artistic tradition. Nourished by the influences of an art that blossomed under the Safavid dynasty (1501-1736) and above all by the painting of the Qadjar dynasty (1789-1925), he paints contemplative still lifes, true contemporary icons, in a timeless fusion between the West and the East. His practice crystallises this long cultural dialogue between Europe and Iran, which has been going on since the 17th century.Alijani's formal borrowings from Qadjar art mainly concern still life, in the wake of Mirza Baba. His obstinate and patient gesture creates meditative hybrids whose objects - bowls of fruit, vases, flowers... - seem to haunt an architectural setting, where the human presence is only suggested, even ghostly.

A timeless and spatial veil transpires from his paintings, due in particular to the ambiguity of the decorations or objects, often out of time, sometimes marked by modernity, like the irruption of a vegetable peeler. One can also detect an influence of a little known style of Persian painting, called Farangi Sazi ("The Western Way"). The Farangi Sazi style emerged under Shah Abbas II (1642-1666), in the last decades of the Safavid Empire. It links the East and the West, both by borrowing genres from Western painting (mythological scenes, genre scenes, still lifes, characters dressed in European style) and by using techniques and forms (more naturalism, attention to perspective, lighting, etc.). The use of Western or antique style characters) was not common in the art of Muslim Persia until the 17th century, at least not outside of illuminations. In his still lifes, the artist deploys a sometimes rough, sometimes soft treatment of materials, fabrics and textures. Sometimes we see a drape in the background, revealing a city in the distance, in the manner of an Italian Renaissance painting.

Hadi Alijani is part of this continuity of artistic exchanges between East and West. Thus, just as one finds in Farangi Sazi type paintings figures in togas or gallant scenes in the moonlight, there is in his still lifes a little of the solemnity of Giorgio Morandi's portraits of objects, Giorgio De Chirico's phantasmagorical urban views or Matisse's interiors.However, it is in relation to the work of Cézanne, a respected reference, that the artist maintains the most troubling kinship. He depicts his subjects in an almost floating roundness, where flat tints and reliefs constitute the moving border of a pictorial universe that is humble and yet animated by a plasticity that goes beyond the two-dimensional dimension of painting. Calabashes, coloquintes, utensils and dishes seem to levitate on tables or carpets. Simple, almost familiar in appearance, the settings of his still lifes are nevertheless charged with history. One of the compositions he executed during his residency in Marseille bears witness to this. He combines his usual decorative gourds with a faithful representation of the Pazyryk carpet, the oldest known carpet (woven around the 5th century BC and found in the tomb of a Scythian prince) and a leopard's fur. The meditative power of the still life is thus combined with a tribute to Indo-European history and underlines the pendulum movement it operates between ages and cultures.