Oslo,

SCHWENSENSGATE 1 0170 OSLO NORWAY

20 August 2022 - 11 September 2022

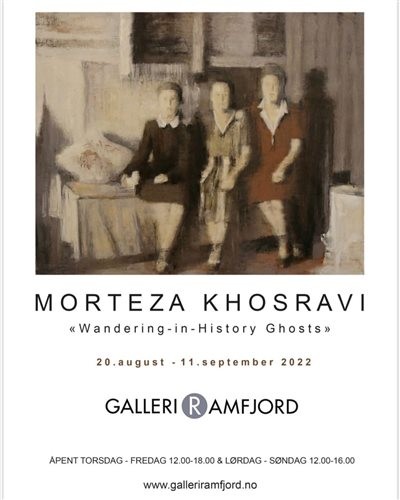

Old photos turn people into objects. They are mummified memories. In such photos, humans are like absent affairs, yet present. Acting in between absence and presence is the feature of each photo. Each face promises its presence at the time and the place. Old photos more precisely represent this acting in between presence and absence, just as photos of the people we know, or family albums – which indicate who is not present anymore – do. The last collection of Morteza Khosravi deals with the same subject. Khosravi is a painter who, in his last collections, dealt with distorted portraiture, and is not afraid of face distortion. His interest in image reconstruction is depicted in Salo Collection which is his personal reconstruction of Pasolini›s film.

In this collection, Khosravi has investigated images of Polish immigrants in Iran. Polish immigrants› involvement in WWII is an event not so much favored by formal history. Polish immigrants are not involved in majorities› narrations, but considered as the narration of minorities. Among all the war immigrants and the displaced, a delipidated cemetery is all left of them, along with few photos. Encountering Polish immigrants› photos is more of a nostalgic encounter than research to a part

of minorities› history. In a nostalgic encounter, we are typically facing an exotic viewpoint which does not depict main facets of an event; it rather beautifies it, turning it into a tourist product to be recorded in history. In such an encounter, humans or victims of war seem as objects.

In this collection, Khosravi has de-objecified photos of humans, leaving out the exotic viewpoint toward the past. He has resurrected the wandering-in-history ghosts in these old photos. The aim

is not solely to represent the same past photos through a painting technique. Painter›s technique serves to ghosts present in historical photos. They are not considered as a historical document in these paintings. The painter leaves aside the documentary aspect of photos, giving them a non-historical soul. If we merely look into the documentary aspect of the photos and try to look for the same in painting, we therefore indicate the absence, reducing the story of Polish immigrants to solely a narration of the lives of absent humans.

In my opinion, the aim of this collection of Khosravi›s is not to look upon the absent humans. He has depicted the presence of those humans with their ghosts in the frame of painting. This presence is not bound to a date or place. They are beyond a specific race. They are the story of the people who come again in history. Implicit references of the painter to the history of art are hereby justified. He has deliberately chosen photos which have inter-pictorial relations with works from history of painting.

Amir Nasri