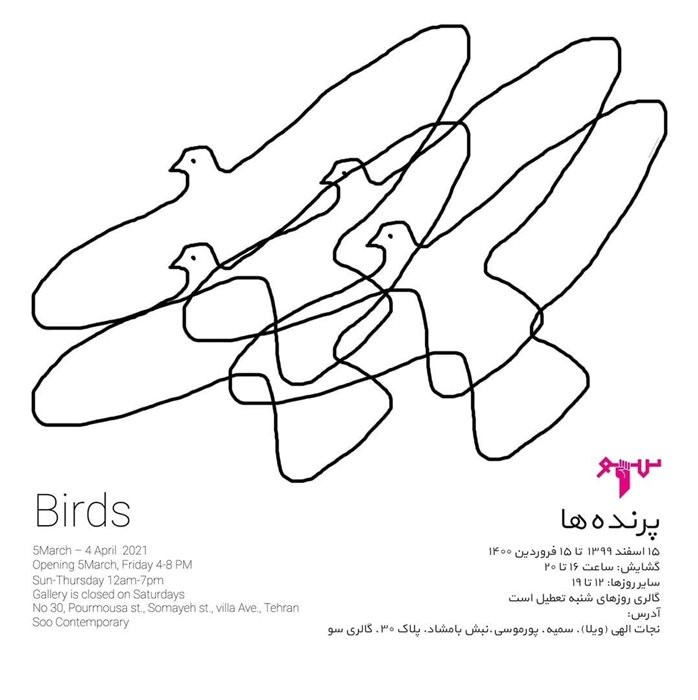

Tehran,

No. 30, Pourmousa Ave., Somayeh St. Villa St.

5 March 2021 - 4 April 2021

Fowl to bird

From the outset, the charming factors of birds to humans were the ultimate difference residing in how they live, their endless beauty, delightful, sometimes odd sound, and their variety from delicate defenseless creatures to hierarchical invaders, as well as the long-lasting regret of man for flying, has dedicated an ocean of meaning in arts and literature to birds in general.

Birds paid their most valuable dividend in Iranian art through their juxtaposition with flowers! “Bird and flower” is an amazing one-of-a-kind style establishing its audience vis-à-vis with ultimate beauty and delicacy, in form or sense. Noble examples of “bird and flower” represent a dialogue between the bird and the flower, the lover and the loved. This pattern possesses an exaggerated grace, is calm and looks spiritual. Though repeated many times, it is extremely differentiated.

As Imam Mohammad Ghazali’s word on beauty, whatever exists in this world, is a reflection of its origin in the universe above. By so defining and accepting ancient criteria of beauty-perfection, enrichment, and purity “bird and flower” could be related to the universe above. A vaster insight would not tie its own hands with these mere factors. Bird painting in Iranian art has been revolutionized by two artists; Kamal-ol-Molk, through his gracious oil paintings from hunted birds perched on top of spears and his astonishing collection of watercolor paintings from royal cage- 19 paintings as a whole album in watercolor being ordered by Naser-e-Din Shah- not only did he not offer a meaningful image, respecting all his learnings from abroad, remained loyal to the form of his subjects.

Second comes Hadi Tajvidi, founder of today’s miniature school of Tehran early this century, who added a contemporary in its Occidental sense approach to Iranian painting. A new window opened to our contemporary painting, still running its course, even if the name “miniature school of Tehran” does not play its vintage role. In one of his art works, Tajvidi has depicted a huge swan beside the lying posture of a naked woman next to a waterfall and lake, which is undeniably one of the most notable works of the last two centuries-both from a taboo breaking aspect and its enlightening role for today’s figurative painting. This swan has not descended from heaven and is too huge to be called a bird! From this point and by placing the pieces of Kamal-ol-Molk’s occidental experience and the half-Iranian approach of Tajvidi, we are observing the contemporary place of bird in Iranian arts-a non-divine meaning, depicted based upon the image itself and the artist’s will.

Apart from the form which is the inseparable component of tendency for depicting birds, the expressions and semantics on this subject are of high attention and notice. On the surface, birds are defined by freedom and emancipation, leaving the cage an opponent for this notion. Other perspectives of occidental and oriental cultures have specifically defined some birds for us, in short: swallow, symbolizes migration and resurrection; owl, a bad omen and later, wisdom; woodpecker, war and research; crow is a symbol of joy and good news, and the wing itself as a symbol of power and protection. However, in contemporary arts, any image could be independently subject to the artist’s personal interpretation, even deprived of any meaning.

In Iran, from the eminent presence of birds in classic literature and poetry, such as the phoenix and Mantegh-O-Teyr, as well as the variety of birds in different cities and their migration in certain stretches of the year, to having birds at home, seeing omen dragging love birds, have all constructed a deep collective memory, so that even if with deep sorrow- no stork comes to Tajrish, or Miyankaleh is no longer as crowded as it used to be by birds, still birds with great variety keep flying in the sky of Iranian art, indefatigably and relentlessly.

From the outset, the charming factors of birds to humans were the ultimate difference residing in how they live, their endless beauty, delightful, sometimes odd sound, and their variety from delicate defenseless creatures to hierarchical invaders, as well as the long-lasting regret of man for flying, has dedicated an ocean of meaning in arts and literature to birds in general.

Birds paid their most valuable dividend in Iranian art through their juxtaposition with flowers! “Bird and flower” is an amazing one-of-a-kind style establishing its audience vis-à-vis with ultimate beauty and delicacy, in form or sense. Noble examples of “bird and flower” represent a dialogue between the bird and the flower, the lover and the loved. This pattern possesses an exaggerated grace, is calm and looks spiritual. Though repeated many times, it is extremely differentiated.

As Imam Mohammad Ghazali’s word on beauty, whatever exists in this world, is a reflection of its origin in the universe above. By so defining and accepting ancient criteria of beauty-perfection, enrichment, and purity “bird and flower” could be related to the universe above. A vaster insight would not tie its own hands with these mere factors. Bird painting in Iranian art has been revolutionized by two artists; Kamal-ol-Molk, through his gracious oil paintings from hunted birds perched on top of spears and his astonishing collection of watercolor paintings from royal cage- 19 paintings as a whole album in watercolor being ordered by Naser-e-Din Shah- not only did he not offer a meaningful image, respecting all his learnings from abroad, remained loyal to the form of his subjects.

Second comes Hadi Tajvidi, founder of today’s miniature school of Tehran early this century, who added a contemporary in its Occidental sense approach to Iranian painting. A new window opened to our contemporary painting, still running its course, even if the name “miniature school of Tehran” does not play its vintage role. In one of his art works, Tajvidi has depicted a huge swan beside the lying posture of a naked woman next to a waterfall and lake, which is undeniably one of the most notable works of the last two centuries-both from a taboo breaking aspect and its enlightening role for today’s figurative painting. This swan has not descended from heaven and is too huge to be called a bird! From this point and by placing the pieces of Kamal-ol-Molk’s occidental experience and the half-Iranian approach of Tajvidi, we are observing the contemporary place of bird in Iranian arts-a non-divine meaning, depicted based upon the image itself and the artist’s will.

Apart from the form which is the inseparable component of tendency for depicting birds, the expressions and semantics on this subject are of high attention and notice. On the surface, birds are defined by freedom and emancipation, leaving the cage an opponent for this notion. Other perspectives of occidental and oriental cultures have specifically defined some birds for us, in short: swallow, symbolizes migration and resurrection; owl, a bad omen and later, wisdom; woodpecker, war and research; crow is a symbol of joy and good news, and the wing itself as a symbol of power and protection. However, in contemporary arts, any image could be independently subject to the artist’s personal interpretation, even deprived of any meaning.

In Iran, from the eminent presence of birds in classic literature and poetry, such as the phoenix and Mantegh-O-Teyr, as well as the variety of birds in different cities and their migration in certain stretches of the year, to having birds at home, seeing omen dragging love birds, have all constructed a deep collective memory, so that even if with deep sorrow- no stork comes to Tajrish, or Miyankaleh is no longer as crowded as it used to be by birds, still birds with great variety keep flying in the sky of Iranian art, indefatigably and relentlessly.