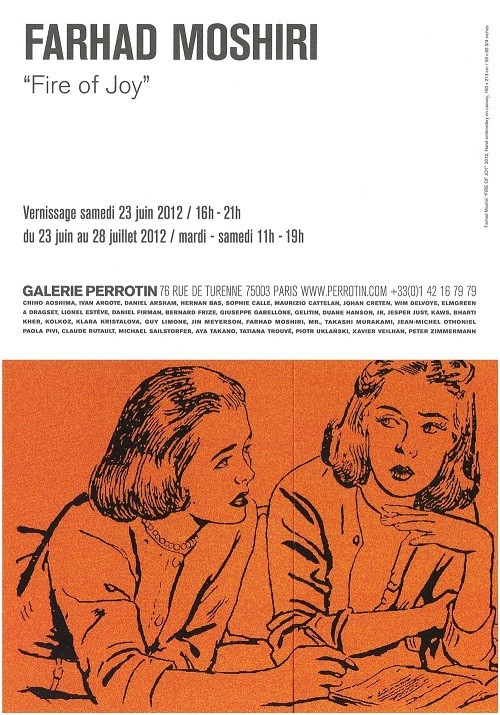

Paris,

PARIS MARAIS 76 RUE DE TURENNE 75003

23 June 2012 - 28 July 2012

FARHAD MOSHIRI - FIRE OF JOY

BY MICHELE ROBECCHI

BY MICHELE ROBECCHI

Life is primarily dominated by a hunting instinct, and predators are distinguishable in nature because of the position of their eyes. Eyes are in the front of the head, to aid pursuit. Prey animals’ eyes are found on the side, to search for predators. When transferred to visual art, as the renowned playwright David Mamet has once astutely observed, the hunting process is actually shared between the creator and the audience.

The viewer is told what the goal is, and like the artist, works to determine what happens through observation. Art is not, though it may appear to be, just the mere presentation of an idea but the inculcation in the audience of the instincts that generated it. Interpretation, in short, engages the

same portion of the brain used for the hunt.

When it comes to Farhad Moshiri’s work, however, a singular phenomenon takes place where the artist comes across both as hunter and prey. Hunter because his visual vocabulary is extraordinarily rich – indiscriminately picking up from a wide range of influences that include pop art, conceptual art, comics, advertising, classic portraits and religious iconography, and subjecting them to a treatment that embraces an equal variety of media, from painting to embroidery and sculpture. And prey because Moshiri, although steadily projected onto the exploration and experimentation of new formal possibilities and ideas, is also persistently reiterating his own work, almost haunted by his younger self, always there over his shoulder whispering in his ears what to do and what not to do. In this

fascinating process, chance naturally plays a pivotal role. If Moshiri has managed over the years to reference the history of art while successfully avoiding the trap of derivativism or citationism, it is because a large part of his practice is open to external factors that have very little to do with

art per se and a lot to do with day-to-day life. In plain contemporary art jargon these elements have been often referred to as ‘ordinary objects’, but in Moshiri’s work such definition is restrictive if misplaced, as it is a well-proven fact that no object in itself can be considered just ‘ordinary’

or banal. Old refrigerators, kitchen knives, vintage pieces of furniture, wooden chairs, pottery, key fobs and other paraphernalia are products of a modern civilization, and carry with them a luggage of cultural implications that duly emerge in temporal and geographical distance – a fact repetitiously demonstrated from impressionism to Jeff Koons via Oldenburg and Warhol. Koons in particular is acknowledged for taking to a new level the introduction and general acceptance of the kitsch side of popular culture to a sophisticated audience but it should be noted that such exercise, which is fundamentally based on the idea of increasing scales, emphasizing ornaments and amplifying sentiments like fear and joy, is deeply rooted in history, and found its early expressions in Western movements like Baroque and Mannerism. Baroque in this case is especially pertinent as its proliferation set the maiden example of how, in a time of crisis as the one faced by the Catholic Church in 1600 due to the rise of Protestantism, exaggeration is the weapon of choice when it’s necessary to reinforce the notion of propaganda. This is particularly visible in works like God (2012), a multicoloured patchwork made of embroidered canvases where the word ‘God’, repeated 42 times, comes out like a neon light

flashing, or See God in Everyone (2012), where the encouraging slogan looks like a stereogram – readable from a distance but completely lost in the detailed amass of key chains that compose it if viewed at close sight.

Such a blatant promotional tactic, which in a street context put religion on the same level as the most trivial product advertisements, is no rarity in Anglophone countries, where religion is called to deal with an increasing erosion of its power. But once transferred to Islamic visual heritage, where religion is still of major importance and which is notoriously conspicuous for the absence of any form of iconography, the same concept is tackled by a radically different problematic, and one that would have

theoretically made strong advocators of purity of form like Adolf Loos happy, namely the postulation of ornament as something useless and meaningless. As Moshiri himself has pointed out, ‘In Islam you’re not supposed to do figurative art. Therefore ornamentation was promoted and nurtured in order not to say anything. There is a lot of talk about the idea that in Islam you’re not supposed to do figurative art. […] Abstract art is a safe art, as far as Islam is concerned. It is easy on the eye and it’s harmless. It is neither social nor political.’ Both supporters of abstraction and ornamentation would scoff at the idea that their elected media present a communion of intents, but if viewed again in religious terms, where

contrasting tools are selected to accomplish the same goal, the association is not as puzzling as it might sound. Abstraction and ornamentation share the purpose of distorting reality, and by introducing ornament in his art, Moshiri took the proverbial challenge of trying to convey a message by deploying something largely perceived as unavailing while adopting at the same time existing objects and images that would grant him a degree of freedom from the accusation of coming up with an allegedly prohibited imagery on his own. In this sense, Moshiri’s approach is in fact significantly liberating. Pop culture is after all a quintessentially inclusive creature, and one of its basic functions is to show people that there are many options available and to choose which one is right for them. Moshiri’s versatility

could be superficially interpreted as a visual gimmick, but in reality it is a smart and highly progressive operation, designed to break down some of the barriers that inhibit a large portion of the society he belongs to on the one hand while reaching out to one which has the tendency of seeking recognizable signals of cultural and geographical provenience when confronted by an art outside its regional scope on the other.

Here it is necessary to pause, and reflect on the level of expectations normally placed on artists with a background considered fertile terrain for political engagement. It is an assumption that transcends the simple notion of an art made to measure for the exercise of Western exoticization of other countries, and revolves more around the idea that an art not openly connected or militant about the political issues that govern the conversation of the area where is produced is an art living way below its

possibilities. Following this logic, Morshiri’s decision to relocate to his native Iran after a spell of twelve years in the States makes him the ideal candidate for the role – a local correspondent with a sound knowledge of the requirements of his audience. His commitment to customary feminine techniques like embroidery or the utilization of a material immediately and transversally quantifiable as gold, coupled with the aspiration to incorporate and overlap some of the most accessible components from the two cultures that make up his biography, nevertheless results in a feeling of displacement that is immediately visible in his work. Images like Mystery Man (2012) or Invisible Driver (2012) challenge the reassuring premise they propose by erasing or covering the face of the subjects, raising issues of censorship or highlighting the disturbing prospect of being guided by a force whose identity remains a secret. Despite referencing dramatic scenarios, both works maintain a strange, viewer-friendly joyous

tone. This is not accidental as Moshiri has individuated a long time ago in lightheartedness a much more effective communication tool to criticize the obsessive pursuit of happiness that characterizes contemporary society, as well as the ideal place to hide his dry sarcasm. And yet, despite this apparent gaiety, he is also capable of intense dark moments. Knives, objects that by any standard present a poignant association with violence and that couldn’t be more remote from the grace that distinguishes

embroidery, have over the years become one if his signature media, and if they occasionally maintain a relatively bright, functional presence, as in the beaming Raw and Silver Knife on Gold Frosting (2012), they fully express their dramatic authority in an installation like Quiet (2012), a collection of 21 classic 20th-century European-style portraits in a moderately lit room whose austerity is emphasized but also questioned by the line of knives that transfix them, forming the authoritative word ‘Quiet’.

The possibility of the viewer to elaborate the ideas suggested by the artist, the diversification of techniques and references, and the huge repertoire of popular items drawn from an aesthetic related to the bazaar or the mall, are all ingredients that converge into the aforementioned general sense of

displacement, and testify that Farhad Moshiri’s art, in its perennial state of transformation, perfectly mirrors the ambiguities and the paradoxes of a society constantly at odds with itself in its quest for coming to terms with the tumultuous times it is living.

1 See David Mamet, Theatre, Faber & Faber, London, 2010.

2 Farhad Moshiri, ‘An Artified World: Interview with Jérôme Sans’,

in Farhad Moshiri, Ropac, Janssen, The Third Line and Perrotin, 2010.

3 During his stay at the California Institute of Arts, Moshiri spent some time with

John Baldessari, whose pioneering methods of accumulation, archivation, and

language use were to have a lasting influence on him.