- La Mise Au Tombeau (The Entombment) 1926

- Oil on canvas

- Painting

- 75 * 57 cm

- signed and dated "M. SAID 1926" (lower left)

Framed

The present work is included in the Artists Catalogue Raisonne; Valerie Didier Hess and Hussam Rashwan, Mahmoud Said: Catalogue Raisonne Volume 1, Paintings, Skira Editore, 2016, numbered P91

Estimation

£350,000

438,982 USD

-

£500,000

627,117 USD

Realized Price

£630,300

790,543 USD

48.306%

Artwork Description

LE MISE AU TOMBEAU, A MASTERPIECE BY MAHMOUD SAID DESCRIBED AS "ONE OF HIS MOST STRIKING PAINTINGS" BY THE ARTISTS CATALOGUE RAISONEE, FORMERLY ON LOAN TO THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, ALEXANDRIA

"For the Primitive artist, the problem is not to conquer the form but rather to renounce form in favour of a spectacular orchestration of the figures and colours. La Mise Au Tombeau established the wave of Primitivism that shaped itself around Mahmoud Said's core work. "

- Henri El Kayem, La Revue du Caire, No.43, Cairo, June 1942 pp.112

"The penetrating humanity of the Flemish Primitives had a strong effect on him, and one of his most striking paintings capturing this deep emotion was La Mise au Tombeau"

- Valerie Didier, Mahmoud Said, Catalogue Raisonne

Bonhams are proud to present one of the most important and emotive works by the doyen of Egyptian art, Mahmoud Said, ever to come to the market. Described as one of the artists most "striking paintings" by the artists catalogue raisonne, and a work central to "shaping" the artists "core work" by critics at the time, La Mise Au Tombaeu, painted in 1926, comes from a critical period in Said's artistic development, when the artist was transitioning from academic portraiture and landscape painting to his signature empathetic renderings of Egyptian daily life.

Said's stylized representations of Egyptian life, pronounced so touchingly in the present work, would later be regarded as the supreme expression of Egyptian artistic heritage in the twentieth century. The present work is widely recognised as his first painting with a religious or spiritual subject matter and sparked a period of creativity in the late 1920's when the artists most significant and iconic paintings were produced.

Most likely depicting the famous Cairo necropolis (al-Qarafa), a sprawling centuries old cemetery home to elaborate tombs and mausoleums from the Mamluk and Fatimid empires, Said's work is part of a long and illustrious tradition of Egyptian funerary art stretching back millennia when ancient Egyptian society had a distinct preoccupation with funerary rites and the afterlife.

Said however, identifies more immediate inspiration pointing to the Western canon of Christian entombment paintings and specifically the Flemish Primitive painters and Tintoretto, whose visual schema Said incorporates into a distinctly Egyptian scene imbuing a sense of heroism and grandeur to the suffering of his essentially anonymous characters.

The present work comes to market with a distinguished provenance; originally in the collection of the artist's daughter, it was on loan for a period to the museum of Fine Arts in Alexandria and exhibited there twice during Said's major retrospectives in the 1960's. Published in nearly a dozen books and journals, and exhibited on numerous occasions, La Mise au Tombeau's immense significance is underscored by its extensive commentary in both contemporary and present sources.

Never before presented at auction, La Mise au Tombeau is an extremely rare example of a major narrative scene coming to market. With the majority of Said's work held by institutions or in permanent collections, the current sale presents collectors with one of the few remaining opportunities to acquire a pivotal work by the artist.

""The penetrating humanity of the Flemish Primitives had a strong effect on him, and one of his most striking paintings capturing this deep emotion was La Mise au Tombeau. The expressive body language of the figures, depicted with such emotional intensity, communicates the tragedy of the scene and the characters distress in a similar way as achieved by Rogier van der Weyden in his renowned panel painting the Descent of the Cross.

To some extent, Said's entombment scene, which appears to be taking place in a Muslim cemetery, unmistakably in Egypt and most likely in Alexandria, can be viewed as the quintessentially Egyptian counterpart to the Christian representations of a scene from the Passion of Christ, that of the Entombment of Christ, as painted by Trecento and Quattrocento Italian masters such as Simone Martini and Giotto.

This particular biblical subject seems to have struck Said, as he wrote to Beppi Martin that although the "baroque" Venetian painters such as Verone and Tintoretto did not appeal much to him, Tintoretto's interpretation of the Entombment of Christ that he saw in the Capella dei Morti in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice "caught my eye because of its wide range of colours, although subtle".

Once again, Said innovatively adapted the traditional Christian iconography of Christ's entombment by interpreting it with his very own Egyptian vernacular in La Mise au Tombeau, setting the scene in a familiar Egyptian environment with a sky invaded by his signature black birds, the messengers of death.

Rather than making it a "pastiche" of European Primitive art, that seemed to bother some art critics such as Jean Moscatelli, Said revolutionized the stylistic and iconographic Western conventions by answering them with a common yet emotionally charged scene of everyday life in Egypt"

Valerie Didier, Mahmoud Said Catalogue Riasonne, Vol 1, P.129

La Mise Au Tombeau is part of a long and illustrious tradition of Egyptian funerary art stretching back millennia when ancient Egyptian society had a distinct preoccupation with funerary rites and the afterlife.

The funerary practises that Said depicts are principally Islamic, with the body wrapped in a white kafan prior to being buried, and the funerary procession leading from the mosque to the burial ground after the janazah (funerary prayers) have taken place.

In addition to this, several unique elements of ancient Egyptian culture still permeate Egyptian belief; namely a belief that the soul of the dead visits the grave multiple times. The soul returns firstly on the third day and then consecutively seven, fifteen and forty days after death. Additionally, Egyptians believe that the soul will continue returning every Friday. Connecting that with Islamic beliefs, the spirit of the prophet also visits the grave in order to smell the aloe plant that is often found next to graves.

The most astonishing similarity, though, between ancient and modern Egyptian funeral practices, and one highlighted in Said's painting, is in regards to mourning. Specifically, after the one's death, their female loved ones take it upon them to become professional mourners.

Displays of grief could be very intense for both familial and professional mourners and Said's sympathetically rendered female figure exemplifies this. Almost identical lamentations took place during the funeral of Ramose, a vizier during the 18th Pharaonic Dynasty (around 1400BC) where contracted women were screaming loudly, weeping and tearing their clothes off.

"For the Primitive artist, the problem is not to conquer the form but rather to renounce form in favour of a spectacular orchestration of the figures and colours. La Mise Au Tombeau established the wave of Primitivism that shaped itself around Mahmoud Said's core work. "

- Henri El Kayem, La Revue du Caire, No.43, Cairo, June 1942 pp.112

"The penetrating humanity of the Flemish Primitives had a strong effect on him, and one of his most striking paintings capturing this deep emotion was La Mise au Tombeau"

- Valerie Didier, Mahmoud Said, Catalogue Raisonne

Bonhams are proud to present one of the most important and emotive works by the doyen of Egyptian art, Mahmoud Said, ever to come to the market. Described as one of the artists most "striking paintings" by the artists catalogue raisonne, and a work central to "shaping" the artists "core work" by critics at the time, La Mise Au Tombaeu, painted in 1926, comes from a critical period in Said's artistic development, when the artist was transitioning from academic portraiture and landscape painting to his signature empathetic renderings of Egyptian daily life.

Said's stylized representations of Egyptian life, pronounced so touchingly in the present work, would later be regarded as the supreme expression of Egyptian artistic heritage in the twentieth century. The present work is widely recognised as his first painting with a religious or spiritual subject matter and sparked a period of creativity in the late 1920's when the artists most significant and iconic paintings were produced.

Most likely depicting the famous Cairo necropolis (al-Qarafa), a sprawling centuries old cemetery home to elaborate tombs and mausoleums from the Mamluk and Fatimid empires, Said's work is part of a long and illustrious tradition of Egyptian funerary art stretching back millennia when ancient Egyptian society had a distinct preoccupation with funerary rites and the afterlife.

Said however, identifies more immediate inspiration pointing to the Western canon of Christian entombment paintings and specifically the Flemish Primitive painters and Tintoretto, whose visual schema Said incorporates into a distinctly Egyptian scene imbuing a sense of heroism and grandeur to the suffering of his essentially anonymous characters.

The present work comes to market with a distinguished provenance; originally in the collection of the artist's daughter, it was on loan for a period to the museum of Fine Arts in Alexandria and exhibited there twice during Said's major retrospectives in the 1960's. Published in nearly a dozen books and journals, and exhibited on numerous occasions, La Mise au Tombeau's immense significance is underscored by its extensive commentary in both contemporary and present sources.

Never before presented at auction, La Mise au Tombeau is an extremely rare example of a major narrative scene coming to market. With the majority of Said's work held by institutions or in permanent collections, the current sale presents collectors with one of the few remaining opportunities to acquire a pivotal work by the artist.

""The penetrating humanity of the Flemish Primitives had a strong effect on him, and one of his most striking paintings capturing this deep emotion was La Mise au Tombeau. The expressive body language of the figures, depicted with such emotional intensity, communicates the tragedy of the scene and the characters distress in a similar way as achieved by Rogier van der Weyden in his renowned panel painting the Descent of the Cross.

To some extent, Said's entombment scene, which appears to be taking place in a Muslim cemetery, unmistakably in Egypt and most likely in Alexandria, can be viewed as the quintessentially Egyptian counterpart to the Christian representations of a scene from the Passion of Christ, that of the Entombment of Christ, as painted by Trecento and Quattrocento Italian masters such as Simone Martini and Giotto.

This particular biblical subject seems to have struck Said, as he wrote to Beppi Martin that although the "baroque" Venetian painters such as Verone and Tintoretto did not appeal much to him, Tintoretto's interpretation of the Entombment of Christ that he saw in the Capella dei Morti in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice "caught my eye because of its wide range of colours, although subtle".

Once again, Said innovatively adapted the traditional Christian iconography of Christ's entombment by interpreting it with his very own Egyptian vernacular in La Mise au Tombeau, setting the scene in a familiar Egyptian environment with a sky invaded by his signature black birds, the messengers of death.

Rather than making it a "pastiche" of European Primitive art, that seemed to bother some art critics such as Jean Moscatelli, Said revolutionized the stylistic and iconographic Western conventions by answering them with a common yet emotionally charged scene of everyday life in Egypt"

Valerie Didier, Mahmoud Said Catalogue Riasonne, Vol 1, P.129

La Mise Au Tombeau is part of a long and illustrious tradition of Egyptian funerary art stretching back millennia when ancient Egyptian society had a distinct preoccupation with funerary rites and the afterlife.

The funerary practises that Said depicts are principally Islamic, with the body wrapped in a white kafan prior to being buried, and the funerary procession leading from the mosque to the burial ground after the janazah (funerary prayers) have taken place.

In addition to this, several unique elements of ancient Egyptian culture still permeate Egyptian belief; namely a belief that the soul of the dead visits the grave multiple times. The soul returns firstly on the third day and then consecutively seven, fifteen and forty days after death. Additionally, Egyptians believe that the soul will continue returning every Friday. Connecting that with Islamic beliefs, the spirit of the prophet also visits the grave in order to smell the aloe plant that is often found next to graves.

The most astonishing similarity, though, between ancient and modern Egyptian funeral practices, and one highlighted in Said's painting, is in regards to mourning. Specifically, after the one's death, their female loved ones take it upon them to become professional mourners.

Displays of grief could be very intense for both familial and professional mourners and Said's sympathetically rendered female figure exemplifies this. Almost identical lamentations took place during the funeral of Ramose, a vizier during the 18th Pharaonic Dynasty (around 1400BC) where contracted women were screaming loudly, weeping and tearing their clothes off.

More lots by Mahmoud Said

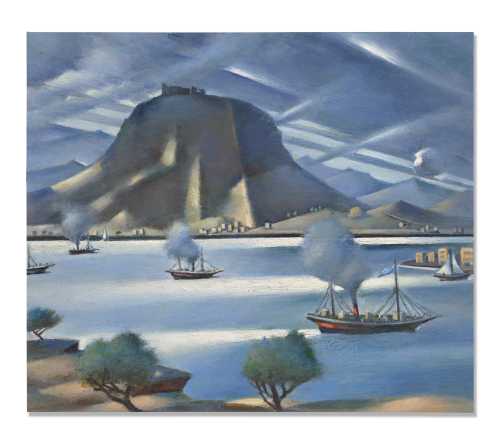

Vue de la plage à Cassata en Grèce (View of the beach in Cassata in Greece)

Estimation

£250,000

322,497 USD

-

£350,000

451,496 USD

Realized Price

£844,200

1,089,009 USD

181.4%

Sale Date

Christie's

-

31 October 2024

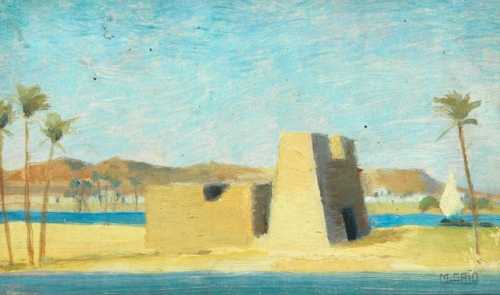

Mekarzel Hill

Estimation

£60,000

78,947 USD

-

£80,000

105,263 USD

Realized Price

£127,000

167,105 USD

81.429%

Sale Date

Christie's

-

6 November 2025

Realized Price

239,929 USD

Min Estimate

79,151 USD

Max Estimate

109,375 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+107.385%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025