- A SILVER-INLAID WHITE BRONZE FOOTED BOWL

- Handicrafts and classics, Metal

- 13.3 cm

- A SILVER-INLAID WHITE BRONZE FOOTED BOWL

IRAN, PROBABLY KHORASSAN, EARLY 13TH CENTURY

On flared foot adorned with a band of animated naskh on a dense scroll ground, the rounded body with alternating medallions and palmettes, the rim with a band of animated kufic against a dense scrolling ground, most silver remaining

7 1⁄2in. (19cm.) diam.; 5 1⁄4in. (13.3cm.) high

Estimation

£30,000

39,484 USD

-

£50,000

65,807 USD

Unsold

Artwork Description

Inscribed with Arabic benedictions, with extra letters.

Around the rim: al-‘izz wa’l-iqbal wa’l-dawla wa’l-salama wa’l-sa‘a a da wa’l-rahma wa’l-raha wa’l-shukra a wa’l-shakira a wa’l-qana‘a wa’l-‘inaya wa’l-baqa li-sahibihi, ‘Glory and prosperity and wealth and well-being and happiness and mercy and ease and gratitude and gratefulness and contentment and favour and long life for its owner’

Around the base the inscription, not all deciphered, includes repetitions of: al-‘izz wa’l-baqa …‘Glory and long life …'

Under the chapter on ‘Western Iran and Fars’, Souren Melikian catalogues two bowls of similar “well-known peculiar shape” to the present example as coming from “Eastern Iran (?)” (Asadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 8th-18th centuries, London, 1982, nos.84 and 85, pp.187-189). In the introduction to the same chapter on he discusses and illustrates another of the same form in the National Museum Tehran, where the inventory indicates an origin in Khorasan (Melikian-Chirvani, op.cit, pp.146-147 and fig.53). All are made of bell-metal or white bronze, whose brittle nature is harder to work but which lends itself to very crisp sharp engraving, as seen here.

The present bowl is the precursor of those examples. While the form is similar, it is larger than the others, with a bowl that is more generous in proportion. The decoration is extremely finely worked, but also demonstrating a wonderful restraint in the contrast between the intricately worked bands and roundels with the completely plain metal ground. The first of the two V&A bowls shows the same arrangement of decoration as seen here, with an upper inscription above a band of roundels alternating with cypress trees on a plain ground (inv.no.564-1878). The present bowl can however be dated to an earlier period and the comparison emphasises how strong and confident the designers could be in the years shortly before the Mongol invasion.

However, a very similar arrangement of roundels alternating with wheat-ear cypress trees is below a benedictory inscription with human-headed hastae found on a jug in the Aron Collection attributed to late 13th or early 14th century Jazira (James Allan, Metalwork of the Islamic World, the Aron Collection, London, 1986, no.4, pp.76-70). As here, the cypress trees are topped and tailed by paired elegant split palmette tendrils. Allan demonstrates how the shape of the jug links it closely to much earlier Syrian prototypes, as well as to inlaid bronze jugs from Siirt and Mosul. The present bowl would indicate an earlier date could be appropriate for the Aron jug, which Allan dates on the basis of links to pottery. Allan also links the jug to a bowl in Naples which shares a similar inscription with our bowl, but is of a form with a foot that is not as elevated or constricted as ours (D. S. Rice, The Wade Cup in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Paris, 1955, pl.XII).

The silver here is very well preserved, with the vast majority remaining in place. The vertical hastae all terminate in human heads, while the occasional slanted ones, for instance for a lam-alif, have animal heads. Exactly this combination is found in the penbox made by Shazi in 1210-11 AD for Majd al-Mulk al-Muzaffar in the Freer Sackler National Museum of Asian Art in Washington D.C. (Esin Atil, W. T. Chase and Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., no.14, pp.102-109) which therefore strongly supports a Khorasani early 13th century attribution.

Around the rim: al-‘izz wa’l-iqbal wa’l-dawla wa’l-salama wa’l-sa‘a a da wa’l-rahma wa’l-raha wa’l-shukra a wa’l-shakira a wa’l-qana‘a wa’l-‘inaya wa’l-baqa li-sahibihi, ‘Glory and prosperity and wealth and well-being and happiness and mercy and ease and gratitude and gratefulness and contentment and favour and long life for its owner’

Around the base the inscription, not all deciphered, includes repetitions of: al-‘izz wa’l-baqa …‘Glory and long life …'

Under the chapter on ‘Western Iran and Fars’, Souren Melikian catalogues two bowls of similar “well-known peculiar shape” to the present example as coming from “Eastern Iran (?)” (Asadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 8th-18th centuries, London, 1982, nos.84 and 85, pp.187-189). In the introduction to the same chapter on he discusses and illustrates another of the same form in the National Museum Tehran, where the inventory indicates an origin in Khorasan (Melikian-Chirvani, op.cit, pp.146-147 and fig.53). All are made of bell-metal or white bronze, whose brittle nature is harder to work but which lends itself to very crisp sharp engraving, as seen here.

The present bowl is the precursor of those examples. While the form is similar, it is larger than the others, with a bowl that is more generous in proportion. The decoration is extremely finely worked, but also demonstrating a wonderful restraint in the contrast between the intricately worked bands and roundels with the completely plain metal ground. The first of the two V&A bowls shows the same arrangement of decoration as seen here, with an upper inscription above a band of roundels alternating with cypress trees on a plain ground (inv.no.564-1878). The present bowl can however be dated to an earlier period and the comparison emphasises how strong and confident the designers could be in the years shortly before the Mongol invasion.

However, a very similar arrangement of roundels alternating with wheat-ear cypress trees is below a benedictory inscription with human-headed hastae found on a jug in the Aron Collection attributed to late 13th or early 14th century Jazira (James Allan, Metalwork of the Islamic World, the Aron Collection, London, 1986, no.4, pp.76-70). As here, the cypress trees are topped and tailed by paired elegant split palmette tendrils. Allan demonstrates how the shape of the jug links it closely to much earlier Syrian prototypes, as well as to inlaid bronze jugs from Siirt and Mosul. The present bowl would indicate an earlier date could be appropriate for the Aron jug, which Allan dates on the basis of links to pottery. Allan also links the jug to a bowl in Naples which shares a similar inscription with our bowl, but is of a form with a foot that is not as elevated or constricted as ours (D. S. Rice, The Wade Cup in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Paris, 1955, pl.XII).

The silver here is very well preserved, with the vast majority remaining in place. The vertical hastae all terminate in human heads, while the occasional slanted ones, for instance for a lam-alif, have animal heads. Exactly this combination is found in the penbox made by Shazi in 1210-11 AD for Majd al-Mulk al-Muzaffar in the Freer Sackler National Museum of Asian Art in Washington D.C. (Esin Atil, W. T. Chase and Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., no.14, pp.102-109) which therefore strongly supports a Khorasani early 13th century attribution.

More lots by Unknown Artist

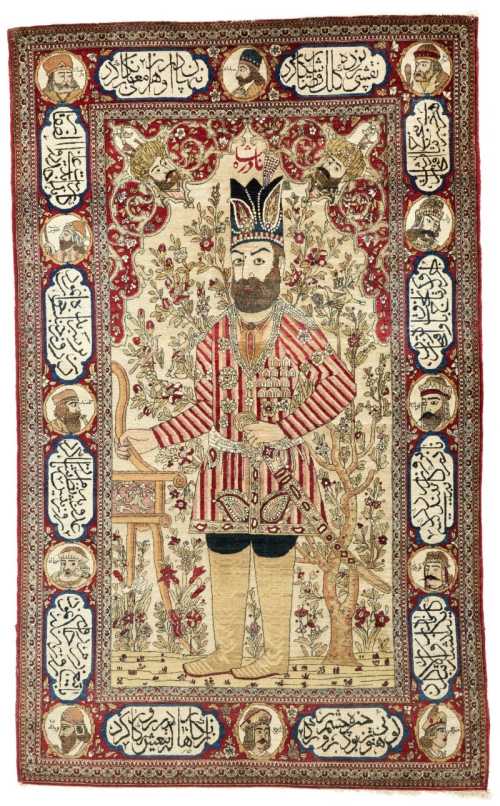

An Isfahan pictorial rug, Central Persia, circa 1910

Estimation

£4,000

5,236 USD

-

£6,000

7,853 USD

Realized Price

£5,670

7,421 USD

13.4%

Sale Date

Sotheby's

-

30 March 2022

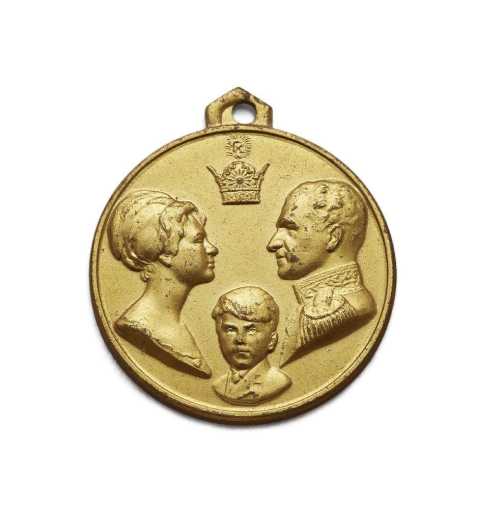

A gold medal commemorating the coronation of Muhammad Reza Shah and Queen Farah

Estimation

£100

132 USD

-

£200

263 USD

Realized Price

£160

211 USD

6.667%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

A silver memorial medal of the White Revolution, Muhammad Reza Shah, 1967

Estimation

£200

263 USD

-

£300

395 USD

Realized Price

£170

224 USD

32%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

Realized Price

67,245 USD

Min Estimate

35,481 USD

Max Estimate

53,247 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+83.63%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

Similar Artworks

A fine Khurasan silver-inlaid bronze inkwell and cover, signed by Abu’l-Sa’d(?) … Shaburi, inscribed with the name Abu’l-Ma’ali Mawdud ibn Ahmad al-‘Asami, Persia, circa 1200

Estimation

£80,000

104,712 USD

-

£120,000

157,068 USD

Sale Date

Sotheby's

-

30 March 2022

A inscribed and inlaid footed bronze bowl, Iran, 13th-14th century

Estimation

£500

658 USD

-

£700

921 USD

Realized Price

£500

658 USD

16.667%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022

A brass openwork shadow sphere, Iran, late 19th century

Estimation

£300

395 USD

-

£400

526 USD

Realized Price

£260

342 USD

25.714%

Sell at

Sale Date

Rosebery's Auction

-

1 April 2022