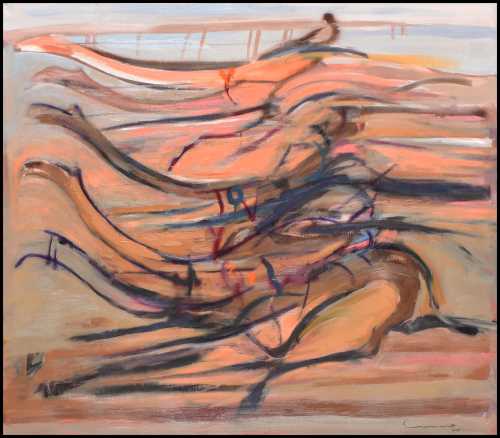

- Untitled 2006

- Acrylic on canvas

- Painting

- 180.3 * 140.5 cm

- signed in Farsi and dated '2006' (lower left)

Artwork Description

Yaghoub Emdadian's paintings are highly abstracted landscapes, where vast spaces are defined in terms of pure forms and variations of colour. Space is arranged in a way that recalls the Persian miniature: unlike the Western depiction of perspective toward a vanishing point, the more distant the location the higher up it is in the composition.

Along the top of Emdadian's paintings one often sees small shapes- trees, buildings, figures. They seem to hang in the far distance, separated from the viewer by large dominant squares of pure colour, which lend a feeling of immensity to this notion of space.

"The photograph had relieved European artists

of the need for optical correctness; they no longer

needed to make pictures, and could now make paintings

infusing their canvases with what and how they felt

rather than with just what they saw and how they saw

it.

Yaghob Emdadians paintings inherit this modernist

counter-tradition associated with the West but so

thoroughly suffused with the seeing processes of Asia

and elsewhere. Indeed, Emdadians work, especially in

its evolution, demonstrates how those seeing processes

have informed the processes of Western modernism. In

his earlier paintings, where the landscape elements

are carefully articulated and unmistakably apparent,

Emdadian modifies the visual literalism of the 19th

century landscape with a luminous palette, a vigorous

brushstroke, and a sense of patterned structure not so

much overlaid on the image as supporting it. These

paintings share a common schema: a cluster of

residences, farmhouses, and other buildings all one

story, most with peaked roofs aligns across a visual

plane near the top of the picture, the horizon line

having been raised to a position barely a quarter of

the way down from the top of the canvas. The rest of

the painting is occupied by a stylized depiction of

fields, scored by mostly diagonal lines.

What read as lines coursing arbitrarily across

(painted or cultivated) fields their orthogonal

thrusts amplified by the pictures high horizons

still seem crucial to the paintings, providing them a

rhythmic and almost tactile frisson. They break up the

plane of vision rather gently, as if rays of sunlight,

and often set off areas of coloristic shimmer,

unlikely effects of water on land, perhaps mirages.

This modified cubism suggests the work of the great

color cubist Jacques Villon, whose lines were

similarly long and pliable and whose colors were

similarly vivid.

As he became more and more abstract through the 1990s,

Emdadian came to embrace a tradition somewhat

different, somewhat more refined, than that of the

cubist landscape. Moving away from any obvious

reference to the real world, he came to inhabit a

world of nearly pure abstraction, in which the

paintings sense of space functioned as one element in

an elaborate counterbalance of visual elements, all of

them apparently liberated from any direct connection

to quotidian observation. The basic schema carries

over verbatim from the earlier, more literal

landscapes: there remains a high horizon, and flecked

upon it are marks suggesting the mid-ground presence

of geometric structures. But now, those structures,

the fields before or below them, and the lines that

mark the fields have all coordinated into a uniplanar

composition, a composition in which only coloristic

nuance allows for a visual comprehension of depth

and an ambiguous depth at that. In fact, that nuance

allows Emdadians colors to move from opaque to nearly

transparent, and to do so within the parameters of

individual shapes, allowing the shapes themselves to

slide back and forth against and upon one another like

sliding doors."

Peter Frank, Yaghob Emdadian: The Spaces of the Land,

Los Angeles, March 2008. Peter Frank is Senior Curator at the Riverside Art Museum in Riverside, California.

Along the top of Emdadian's paintings one often sees small shapes- trees, buildings, figures. They seem to hang in the far distance, separated from the viewer by large dominant squares of pure colour, which lend a feeling of immensity to this notion of space.

"The photograph had relieved European artists

of the need for optical correctness; they no longer

needed to make pictures, and could now make paintings

infusing their canvases with what and how they felt

rather than with just what they saw and how they saw

it.

Yaghob Emdadians paintings inherit this modernist

counter-tradition associated with the West but so

thoroughly suffused with the seeing processes of Asia

and elsewhere. Indeed, Emdadians work, especially in

its evolution, demonstrates how those seeing processes

have informed the processes of Western modernism. In

his earlier paintings, where the landscape elements

are carefully articulated and unmistakably apparent,

Emdadian modifies the visual literalism of the 19th

century landscape with a luminous palette, a vigorous

brushstroke, and a sense of patterned structure not so

much overlaid on the image as supporting it. These

paintings share a common schema: a cluster of

residences, farmhouses, and other buildings all one

story, most with peaked roofs aligns across a visual

plane near the top of the picture, the horizon line

having been raised to a position barely a quarter of

the way down from the top of the canvas. The rest of

the painting is occupied by a stylized depiction of

fields, scored by mostly diagonal lines.

What read as lines coursing arbitrarily across

(painted or cultivated) fields their orthogonal

thrusts amplified by the pictures high horizons

still seem crucial to the paintings, providing them a

rhythmic and almost tactile frisson. They break up the

plane of vision rather gently, as if rays of sunlight,

and often set off areas of coloristic shimmer,

unlikely effects of water on land, perhaps mirages.

This modified cubism suggests the work of the great

color cubist Jacques Villon, whose lines were

similarly long and pliable and whose colors were

similarly vivid.

As he became more and more abstract through the 1990s,

Emdadian came to embrace a tradition somewhat

different, somewhat more refined, than that of the

cubist landscape. Moving away from any obvious

reference to the real world, he came to inhabit a

world of nearly pure abstraction, in which the

paintings sense of space functioned as one element in

an elaborate counterbalance of visual elements, all of

them apparently liberated from any direct connection

to quotidian observation. The basic schema carries

over verbatim from the earlier, more literal

landscapes: there remains a high horizon, and flecked

upon it are marks suggesting the mid-ground presence

of geometric structures. But now, those structures,

the fields before or below them, and the lines that

mark the fields have all coordinated into a uniplanar

composition, a composition in which only coloristic

nuance allows for a visual comprehension of depth

and an ambiguous depth at that. In fact, that nuance

allows Emdadians colors to move from opaque to nearly

transparent, and to do so within the parameters of

individual shapes, allowing the shapes themselves to

slide back and forth against and upon one another like

sliding doors."

Peter Frank, Yaghob Emdadian: The Spaces of the Land,

Los Angeles, March 2008. Peter Frank is Senior Curator at the Riverside Art Museum in Riverside, California.

Realized Price

18,826 USD

Min Estimate

13,200 USD

Max Estimate

18,374 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+16.801%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2020 - 2024

Performance vs. Estimate

2020 - 2024

Sell-through Rate

2020 - 2024

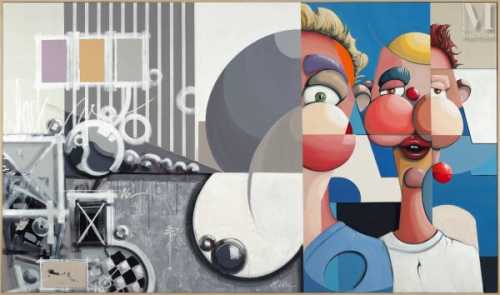

Similar Artworks

Going to Cinderella’s Wedding

Estimation

15,000,000,000﷼

18,750 USD

-

20,000,000,000﷼

25,000 USD

Realized Price

16,500,000,000﷼

20,625 USD

5.714%

Sale Date

Tehran

-

22 May 2025

Why behind my back

Estimation

€14,900

16,227 USD

-

€16,800

18,297 USD

Realized Price

€19,000

20,693 USD

19.874%

Sale Date

Millon & Associés

-

6 July 2023