The works of the great masters are respected in many aspects including their technique, aesthetics and historical importance. Older works of art may seem more powerful due to the death of their creators. Many studies in recent years show that the descriptions of living and dead artists differ from each other. Art prices are often claimed to substantially increase when the artist dies. These claims appear to be largely based on anecdotal evidence. They are promulgated by hearsay and sometimes cleverly insinuated by art dealers who attempt to convince naïve customers that it is justified to mark up the artwork of recently deceased artists.

Around 1660, an Italian art dealer brought bad news to Rembrandt: his style of painting was no longer in vogue and sold at lower prices. Rembrandt did not yield to the art dealer’s suggestion to start painting in the idealizing style of the classic painters, but thought up a cunning plan. He disappeared and had the rumor spread that he had died. As a consequence, works by a “dead” Rembrandt were sold for up to three times the normal price. This anecdote illustrates that the unexpected death of an artist leads to higher prices, a natural consequence of the lower future supply relative to expectations.

Does an artist’s work substantially rise in value in connection with his or her death? Many observers, both casual and professional, believe that this is so. Is there, in short, a “death effect” – which might be defined as a clustered rise in artists’ values, immediately preceding, at, or immediately after the date of death? What is a possible economic rationale for a death effect if one is shown to exist?

Economists have often studied the art market in an attempt to answer the perennial question: Is art a good investment? In order to answer this question however requires an index of art prices over time. It is difficult to provide such an index because art objects are heterogenous and not traded very often. One cannot simply take an average price of all works traded within a particular period or take a basket of art works and calculate the cost of purchasing that basket. This being so two alternative approaches are typically taken to computing the rate of return on paintings over time. The first of these is the hedonic approach in which differences in the characteristics of paintings are controlled for using regression analysis. Variables include things like the dimension of the painting, the materials used, the date of the painting etc. The other technique is the resale method and is a more direct method of calculating the rate of return to art. This approach waits until a painting has been sold twice and then computes the rate of return over the intervening period.

researchers suggest that any death effect in art prices and in collectibles generally is a transient phenomenon caused by renewed interest in the artist’s work following news of their death. They refer to this as the “nostalgia effect” and demonstrate its existence using time series data on the price of sports cards for 13 famous baseball players. The interesting aspect of their study is that the baseball cards are already fixed in supply following the retirement of the player and that changed perceptions regarding the supply of the cards around the time of the players death cannot therefore account for any observed price dynamics. The authors find that there is an increase in the price of cards around the time of a player’s death but that it is short-lived. But whilst this work demonstrates the existence of a “nostalgia effect” it does not say anything about the existence of a death effect associated with the problem of durable monopoly precisely because changed supply conditions are absent in their example.

Whether death affects the price fetched by an artist’s work at auction or not depends in general on supply and demand conditions within the artist’s market. These conditions, moreover, are greatly affected by information concerning the past and probable future conditions of that market. The (flow) demand for an artist’s work is composed of a host of important factors. These factors include the current average price of an artist’s work, on income and income distribution in the relevant market, on the price of alternative investments, on “hype” and advertising,

on expected future price and, most clearly, on tastes. Over the short run, as Frey and Pommerehne have demonstrated, economic factors (joined with factors affecting tastes) may be characterized as affecting prices. Over a longer period, however, the taste parameter creates a tremendous amount of unpredictability and perhaps something even less predictable than a random walk in art markets generally (as Baumol observes). The supply side of the works of any artist or of any particular type of art is also complex. Physical supply obviously consists of all holdings of an artist’s output, including works held by the artists themselves. This would include all items in private collections, in addition to the holdings of museums that are candidates for “deaccessioning”. (Due to pressures of one sort or another, museums rarely deaccession major works). As a flow, an artist’s (or artists’) supply is a function of her rate of output along with some sale rate of the artist’s works at auction and elsewhere. These rates are themselves a function of a host of variables. But at death, an artist’s output ends and a finite quantity of works are (potentially) available for sale in galleries and at auction.

The first investigation that has squarely addressed death-induced art price changes is Ekelund, Ressler and Watson (2000). These authors go some way in providing a theoretical underpinning of the death effect by pointing out that artists produce durable goods under market conditions of monopolistic competition. Thus, given rational actors in the art market, the Coase Conjecture applies (Coase, 1972). Coase’s basic argument is simple. If we assume that some individual (or collection of individuals) is in possession of monopoly control of all the land in America, the monopolist can sell land at rates identified by the demand curve. Assuming that the total amount of land available is fixed, the monopolist would want to sell a monopoly quantity of land and charge the monopoly price for it. A moment’s reflection reveals that a “durable goods monopolist” would not be able to charge more than the competitive price for land sans some kind of guarantee that he would not move further down his demand curve to sell additional quantities of land at lower prices than the monopoly price.

The problem of the durable goods monopolist first described by Coase (1972) is that the monopoly producer cannot sign a contract limiting future production. Then the best thing he can do after having sold a unit is to try and sell another for as high a price as he can obtain. This goes on until the price falls to the marginal cost of production. But consumers will anticipate the fall in price and be unwilling to pay more than the competitive price for the goods. Thus the monopolist forfeits his monopoly power.

Clearly the monopolist must devise some means of guaranteeing buyers that the difference between monopoly and competitive quantities of land will not be sold so as to protect the value of their investment. Coase notes a number of ways that this might be accomplished. Guaranteed “buy-backs”, leasing arrangements and giving away that difference for non-market purposes (public parks, for example) might permit the monopolist to be able to charge monopoly price. Otherwise, the durable goods monopolist cannot behave as a monopolist at all – he must charge the competitive price.

There is an apt analogy to an artist’s output in this simple model. Clearly, the demand and marginal revenue curve of any individual artist is affected by a number of factors, including some expected “normal” rate of output through time. For simplicity we assume that an artist’s output is highly substitutable and that for purposes of analysis, her works in any given medium are homogeneous: the “monopoly element” is thus the style or styles of the particular artist. When production continues over time, “the producer will have to consider the effect his actions have on the expectations of consumers about his actions in future periods”. The value of an artist’s work on the demand side, ceteris paribus, depends on restricted supply. An artist will comply when the loss from doing so does not exceed the gain (over time). But, as Coase points out, “there is no reason why conditions should not be such that it would always pay to disappoint consumers’ expectations of a restriction in output (if they held such expectations) and in such circumstances, output in all periods would be such as to make marginal cost equal to price (i.e., the competitive solution)”. This would occur if some of the arrangements mentioned above (buy-backs, etc.) could not be concluded with consumers.

Artists find themselves in the position of the durable goods monopolist who can only imperfectly make contractual arrangements with demanders of their art. Some such arrangements are possible. Artists who work in “duplicative” media (woodcuts, lithographs, linocuts, prints, etc.) typically limit the edition of particular works, destroying plates at the end of a run as a guarantee to consumers. Additionally, some artists “advertise” that a portion of their output will not enter traditional markets.

In general, however, there are no enforceable and durable arrangements that can be made between artist and demanders to the effect that the artist will not “spoil the market” by some “overproduction” of works. The prospect of this devaluation will, ceteris paribus, keep prices and returns at competitive levels. The potential for devaluation will occur, that is, until the death or the anticipated death of the artist.

During an artist’s lifetime, prices will therefore settle well below the monopoly price. Death, of course, is the ultimate device to commit to discontinuing production. Art prices thus increase when the artist dies because her oeuvre all of a sudden becomes scarcer than originally anticipated. After having laid this theoretical foundation, Ekelund, Ressler and Watson proceed to empirically identify the death effect with the help of a hedonic price regression. Their data consists of a panel of auction records relating to the work of 21 Latin American artists who died near or during the observation period (1977-1996). The prices are shown to peak in the years immediately following an artist’s death, thus lending support to the existence of a death effect.

From a theoretical point of view, the main concern with this pioneering analysis relates to the artists’ age at death. Since the probability of dying increases with age, the information of an old artist’s death is not very surprising and should therefore already be largely reflected in the price, implying a small death effect. The death of an old artist, moreover, causes a relatively small reduction in the anticipated size of her oeuvre which, again, translates into a relatively small price increase when her death is made public. Assuming rational expectations, one would therefore expect the death effect to decrease with the artist’s age at death.

Other studies (2007) acknowledge that the prices of an artist’s works should depend on the expected total supply which, in turn, depends on the artist’s conditional life expectancy at the time of sale. Using a data set comprising auction prices of oil paintings by Danish artists who died during the period 1983-2003, these researchers show that the variable “conditional life expectancy” (which, by definition, assumes the value of zero for artists who are not alive anymore at the time of sale) has a significant negative effect on art prices in their hedonic fixed-effects panel regression, while the dummy variable indicating whether the artist was dead or alive at the time of sale does not appear to have an independent significant influence. These results are compatible with a positive death effect that decreases with the age at death.

Empirical results from a data set comprising more than 400,000 observations show that the relationship between the death effect and the artists’ age at death is inversely u-shaped: the death of young artists actually decreases the price of their works of art, whereas the death effect is positive for older artists and disappears for artist’s who die at a very old age. This pattern perfectly matches the predictions. The negative price effect of untimely deaths, which has not been considered in the literature so far, is a straightforward consequence of reputation-induced demand for works of fine art. The basic mechanism works as follows. At the beginning of their careers, artists have no far-reaching reputation to speak of. Nevertheless, collectors who happen to be familiar with the work of promising young artists might well pay a considerable price for their works of art since they expect these artists to eventually obtain a reputation that justifies the price they pay for the fledgling’s work. If such an artist dies an untimely death, her lifetime oeuvre might not be sufficiently substantial to generate the expected reputation, and the price drops. There are thus two mechanisms determining the death effect: the standard positive effect deriving from unexpected scarcity of supply and a negative effect deriving from frustrated demand-side expectations of artistic reputation. Both effects disappear for artist’s who die at a ripe old age. In conjunction, the scarcity and the reputation effect give rise to the identified inversely u-shaped relationship between death-related price changes and age at death.

.jpg)

Examining the set of variables that are effective in the price of works of art in addition to the effect of death, in parallel with the effect of death, yields interesting results:

- Medium: It is well known that different types of artwork fetch different prices. Results confirm this. Oil on canvas yields the highest prices (+410% as compared to prints), followed by drawings on paper (+80%) and prints.

- Size: We allow for different size effects for oil paintings, drawings on paper, and prints. We make this distinction since large prints are an exception, whereas artists sometimes create extraordinary large paintings and drawings. estimates confirm conjecture that size effects differ across the three media. For prints we find a stable linear relationship between size and price. An increase in height (width) by 10cm raises the price of a print by about 7.2% (3.9%). For oil paintings and drawings on paper, the estimates of the squared regressors become significant. Prices of “reasonably” sized pictures vary positively with size. As one would expect, prices do, however, decline beyond a critical size. This critical size appears to be determined by wall sizes in ordinary collectors’ homes. Paintings and drawings exceeding these dimensions are mainly bought by museums, whose demand is limited. To be more specific: prices of oil paintings increase up to a size of roughly 2.5×4m (height × width), but decline for larger dimensions. The same holds for works on paper whose optimal size in terms of revenue is 3.2 × 3.8m.

- Signature: A signature is a sign of authenticity. As expected, prices increase by roughly +27% if a work of art is signed. The estimate is thus in line with the commonly held belief, but contradicts the finding by Czujack (1997) who cannot detect any positive influence of a signature on the price of Picasso’s works of art. We will return to this issue in the next section when we elaborate on the estimates of quantile regressions.

- Supply: One would expect the actual supply of an artist's work (as measured by the number of pieces auctioned in the respective year) to decrease the market price of her works of art. This expectation is based on the conviction that most collectors are merely interested in owning a representative piece of a certain artist rather than a specific piece. Estimates indeed indicate that an additional supply of 10 pieces per year reduces the market price by about 0.5%. Although this effect is not very large, it indicates that an unusually large actual supply tends to depress prices, or, vice versa, higher prices are fetched in thin markets.

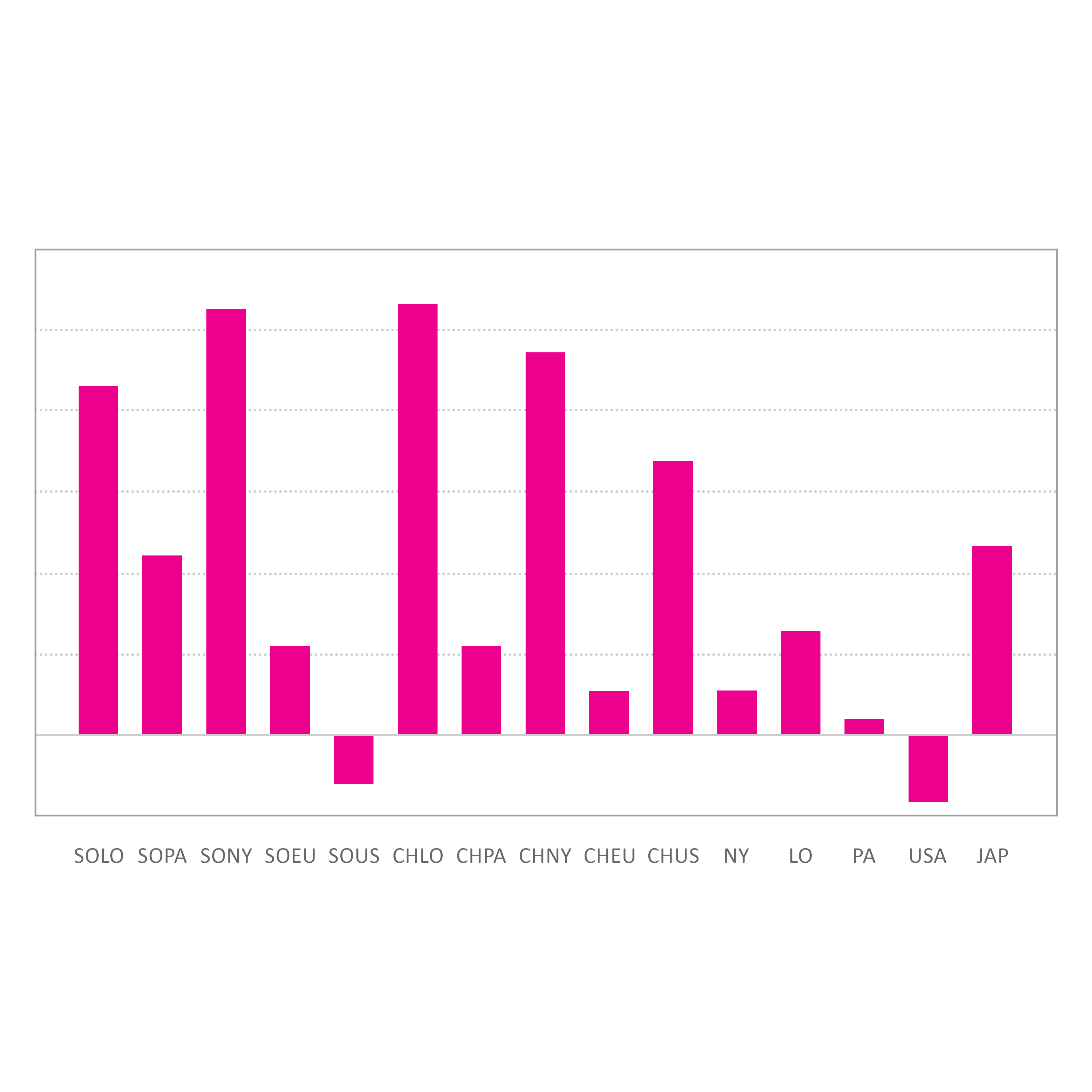

- Country of Sale and Auction House: The influence of the country of sale and of specific salerooms is summarized in Figure 4. All percentage price changes reported in Figure 4 are with respect to a work of art sold in Europe, but not at Sotheby's or Christie's, and not in London or Paris. Sales at Sotheby's New York [+79%] yield higher prices than sales at Sotheby's London [+64%], Sotheby's Paris [+33%], and Sotheby's salerooms in the remaining Europe [+15%]. Sales at Sotheby's US excluding New York fetch even less [-9%]. Unlike Sotheby's, Christie's auctions achieve higher prices in London [+80%] than in New York [+71%], the rest of the US [+50%], Paris [+17%], and the remaining Europe [+7%]. Apart from the two predominant auction houses, we find that prices in London [+19%] are higher than in New York [+8%] and Paris [+2%], and sales in Japan [+35%] fetch more than sales in Europe and the United States [-13%].

Figure 4: Country of Sale and Auction House

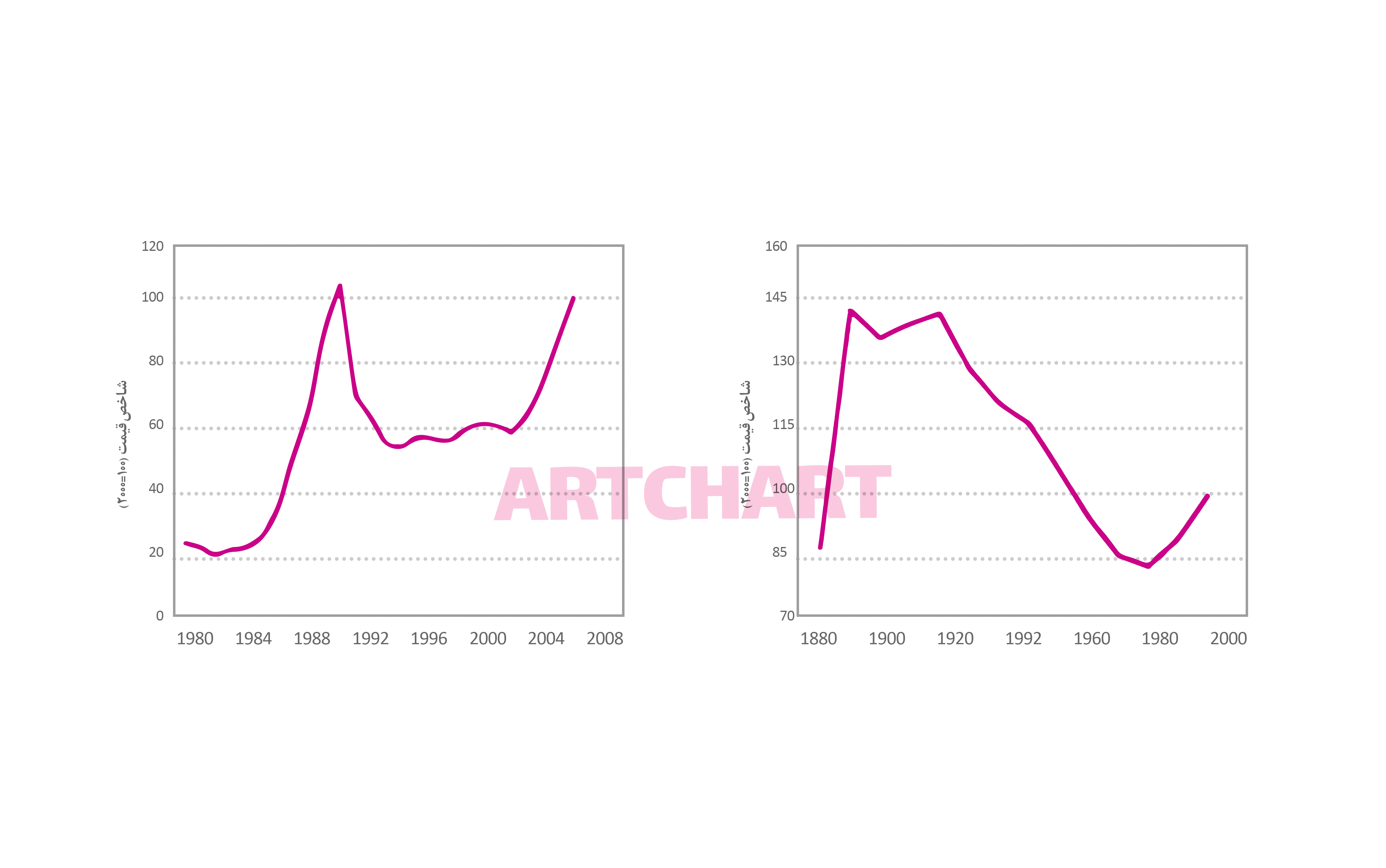

- Price Index: The hedonic art price index which results from the estimated coefficients of the year dummies is depicted in the first panel of Figure 5. The result is well in line with previous findings. In the year 2005 the art prices reached again the level of the last arts market boom in 1990. During the 1990's prices had been rather low and constant.

Figure 5: Hedonic Art Price Index, 1980 -2005, and Creation Period Index

- Genre: The decade in which a work of art has been created is not merely an indicator of age but foremost an indicator of contemporary collectors' tastes for certain periods and genres. The estimated coefficients of the decade dummy variables thus reveal which periods were en vogue during the observation period (1980-2005). The results are summarized in the second panel of Figure 5. Works of art from the period 1890-1920 fetch the highest prices. Prices for works from subsequent periods vary positively with age; only the most recent batch appears to escape this rule, conceivably because contemporary artists are able to produce exactly that kind of art that meets the contemporary collectors' tastes.

It would appear that one is able to predict future price movements on the basis of past price movements and that there is significant serial correlation in the data. Furthermore it is frequently said that old masters enjoy a higher rate of return than contemporary artists of the works of lesser-known artists (although a sequence of papers suggests that the opposite might be true). There also appear to be deviations from the law of one price in which identical prints are sold for different prices days apart with no intervening release of information. Some auction houses appear to obtain consistently higher prices for auctioned paintings, and there is evidence to suggest that art prices are systematically lower in some months than in others.

The direction and the size of the death effect depend on the artist’s age at death. The main theoretical contribution consists in demonstrating that the death effect is negative in the case of an untimely death. This result complements previous theoretical considerations that have focused on death-induced price increases. The negative death effect materializes because it takes a long time to build up a sustainable reputation in the global arts market. Thus, if a promising artist dies before her reputation reaches the level commensurate with the artistic quality of her work, the early collectors’ hopes of owning a piece of art that is generally recognized to represent the value that would actually be justified by the artistic quality, is frustrated. The prices thus decrease after the artist’s death.

Based on research, reputation is a crucial determinant of art prices. Even though this is hardly a novel insight, it is worth emphasizing that the mechanisms underlying the death effect cannot be properly understood without taking the accumulation of reputation into account. the increase in price is principally the result of an increase in the demand for paintings over the immediate post-death period. (A small change in supply could also have occurred). While demand for a particular artist’s work is complex and is a function of a number of variables, the artist’s behavior and the fact that she is living and can vary output rates has a clear effect on demanders’ expectations. The demand side suggests the “death effect”. It is created by certainty concerning one major element of future supplies of a particular artist’s work.

References:

- Heinrich W. Ursprung, Christian Wiermann, (2008) Reputation, Price, and Death: An Empirical Analysis of Art Price Formation.

- Karen Sullivan, Sally Butler, (2017) Are dead artists’ paintings more lively? – Agency in descriptions of artworks before and after an artist’s death.

- R. B. Eklund, Jr. (2000) The “Death-Effect” in Art Prices: A Demand-Side Exploration

- David Maddison, Anders Jul-Pedersen, (2005) The Death Effect in Art Prices: Evidence from Denmark