- Ville Arab (Arab Town) 1950 - 1959

- Oil on canvas

- Painting

- 251 * 197 cm

- framed: 200 by 252.8 cm. 78¾ by 99½ in.

23 March 2022

Estimation

£60,000

79,103 USD

-

£80,000

105,471 USD

Realized Price

£138,600

182,729 USD

98%

Artwork Description

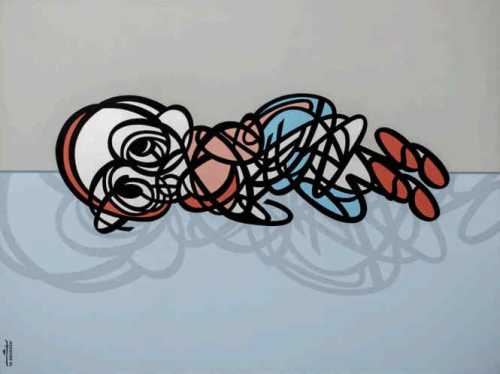

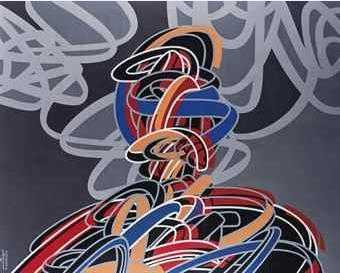

A self-taught son of Egyptian peasants, Hamed Abdalla (1917-1985) was born in Cairo, when the city was still surrounded with agricultural fields. Despite his later and definite departure for Europe, Abdalla was deeply attached to his Egyptian roots. His work demonstrates an affinity with folk Egyptian art, and the children drawings visible on the walls of traditional Cairo (Abaza 2011).

Hamed Abdalla devoted his life and artistic career to searching for new aesthetic conceptions, beyond academic standards and following his own vision. The picturesque landscapes of his Egyptian hometown, the district of Manial in Cairo, were his initial sources of inspiration. There, he absorbed the essence of his cultural heritage to re-transcribe it following a modernized output. Abdalla describes falling captive to the charms of the landscapes, and often painted mud-houses and fellahs from the Egyptian countryside (Dalloul Art Foundation 2020).

“Abdalla’s (…) reinvention of a vernacular or “authentic” language was not based on the invention of a faraway, foreign Other, but on an introspective movement (…) which goes far beyond considerations of (pan-Arabic or Egyptian) identity…”

- MORAD MONTAZAMI IN ARABECEDAIRE, 2018, P.256.

This untitled oil on canvas from the 1950s depicts a traditional house, with a farmer standing in front of the open door and a view on the kitchen. Abdalla painted various similar pieces during this period, such as The House (1953), published in El-Labban & Francis 2016, p.9, or Home (1954), in the Fatma Ismail Collection, Cairo. A variety of pale blue and white tones dominate the composition, in accordance with Abdalla’s belief that these are the colours characterizing the Egyptian palette, due to the dazzling sunlight that softens their intensity (Dalloul Art Foundation 2020). This postulates a direct opposition to Orientalist paintings, which previously mainstreamed warm reds and yellows as the dominant colours of Eastern sceneries. In his quest of emancipation from European structures and methodologies, Abdalla learned to master exaggeration, while diminishing details to contain essential Eastern elements, independent of space (El-Labban & Francis 2016, p.5). The present painting exacerbates the visual flattening that characterized folklore art in early 20th century Egypt and confirms Abdalla’s place as a pioneer of Arab modern art, alongside Raghib Ayyad, Youssef Kamel and Mohammad Nagy.

The 1950s, the period when Abdalla produced this painting, were a time of cultural and intellectual effervescence in Cairo. Yet, the subsequent rise of nationalism and authoritarianism had a profound impact on his career, as it did for many other Egyptian artists. Tired of the political compromises he had to make, Abdalla left Egypt in 1956 for Denmark. This precipitated exile left the artist with a tormented resentment and complex attachment to his land of birth, which are crystallized in his many paintings of the familiar houses that nursed his childhood (El-Labban & Francis 2016, p.10).

More lots by Hamed Abdalla

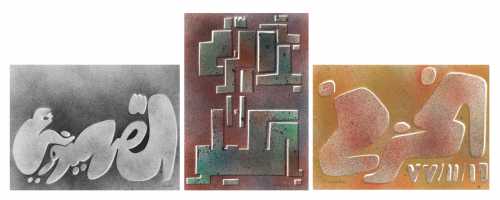

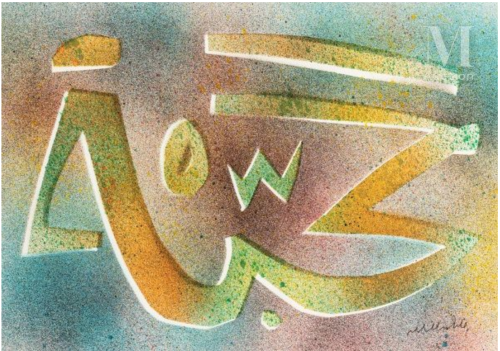

Al Mouhaba (love), from the Talismans series

Estimation

€5,000

6,094 USD

-

€8,000

9,750 USD

Realized Price

€11,700

14,260 USD

80%

Sale Date

Millon & Associés

-

16 June 2021

Realized Price

44,439 USD

Min Estimate

23,286 USD

Max Estimate

33,180 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+44.359%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

Similar Artworks

In The Empire of Sun

Estimation

¥500,000

70,562 USD

-

¥800,000

112,899 USD

Realized Price

¥1,323,000

186,706 USD

103.538%

Sell at

Sale Date

Christie's

-

8 November 2024